FAQs

What is a Japanese sword called?

What is a Japanese sword called?

The Professional Nomenclature of the Japanese Sword

The simple question "What is a Japanese sword called?" belies a vast and nuanced field of study. There is no single answer, as the correct term depends entirely on the specific sword's period of manufacture, morphology, mounting, and intended use. The most accurate and professional generic term is Nihontō (日本刀), which translates to "Japanese sword." This term distinguishes these culturally significant weapons from foreign blades (Yōtō, 洋刀).

However, to truly understand the terminology, one must delve deeper.

1. The Generic Terms: Nihontō and Katana

- Nihontō (日本刀): This is the overarching, scholarly term. It refers to all traditionally made Japanese blades with a curved, single-edged profile, crafted from tamahagane steel using traditional Japanese methods. It encompasses a wide array of types beyond the well-known katana, including tachi, wakizashi, and tantō.

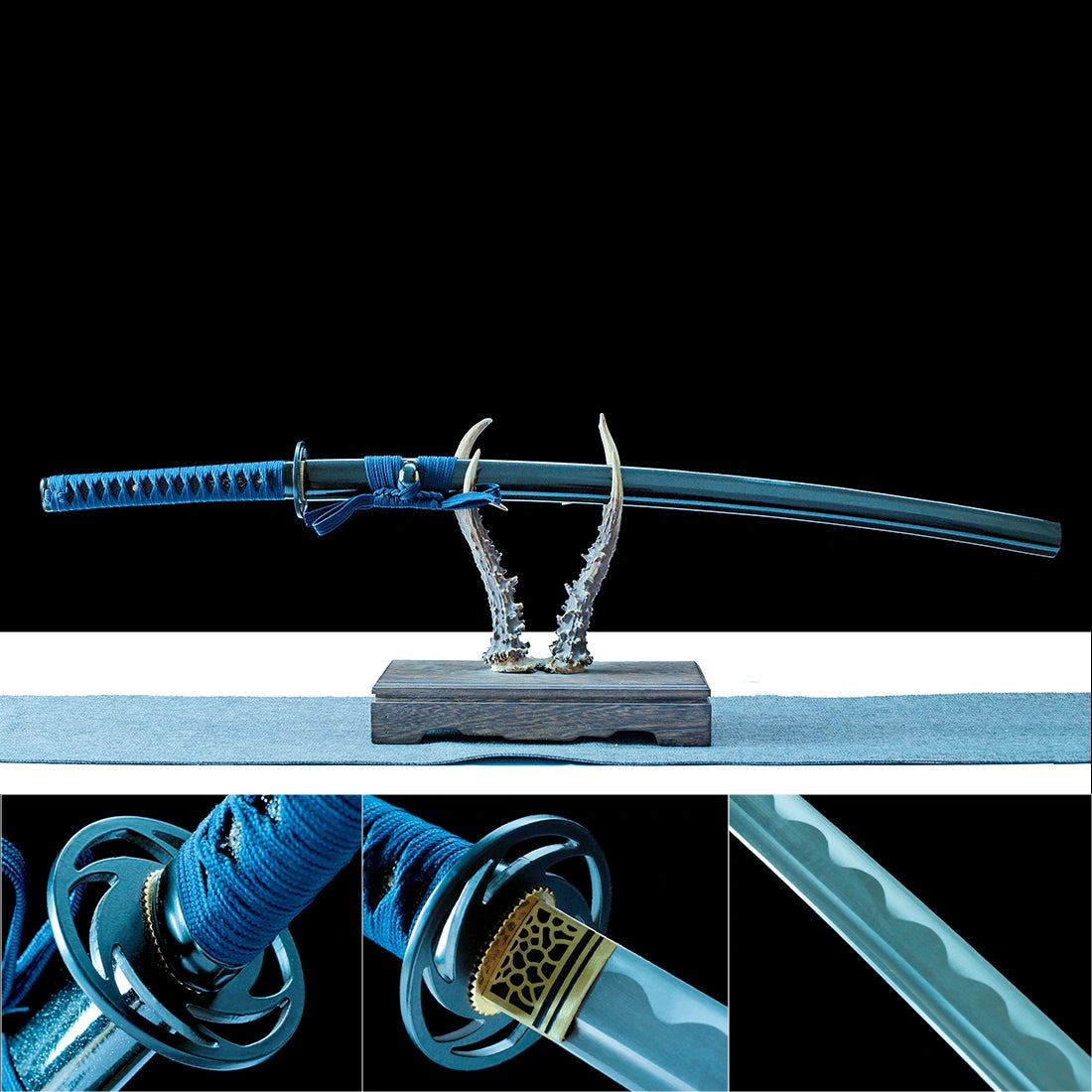

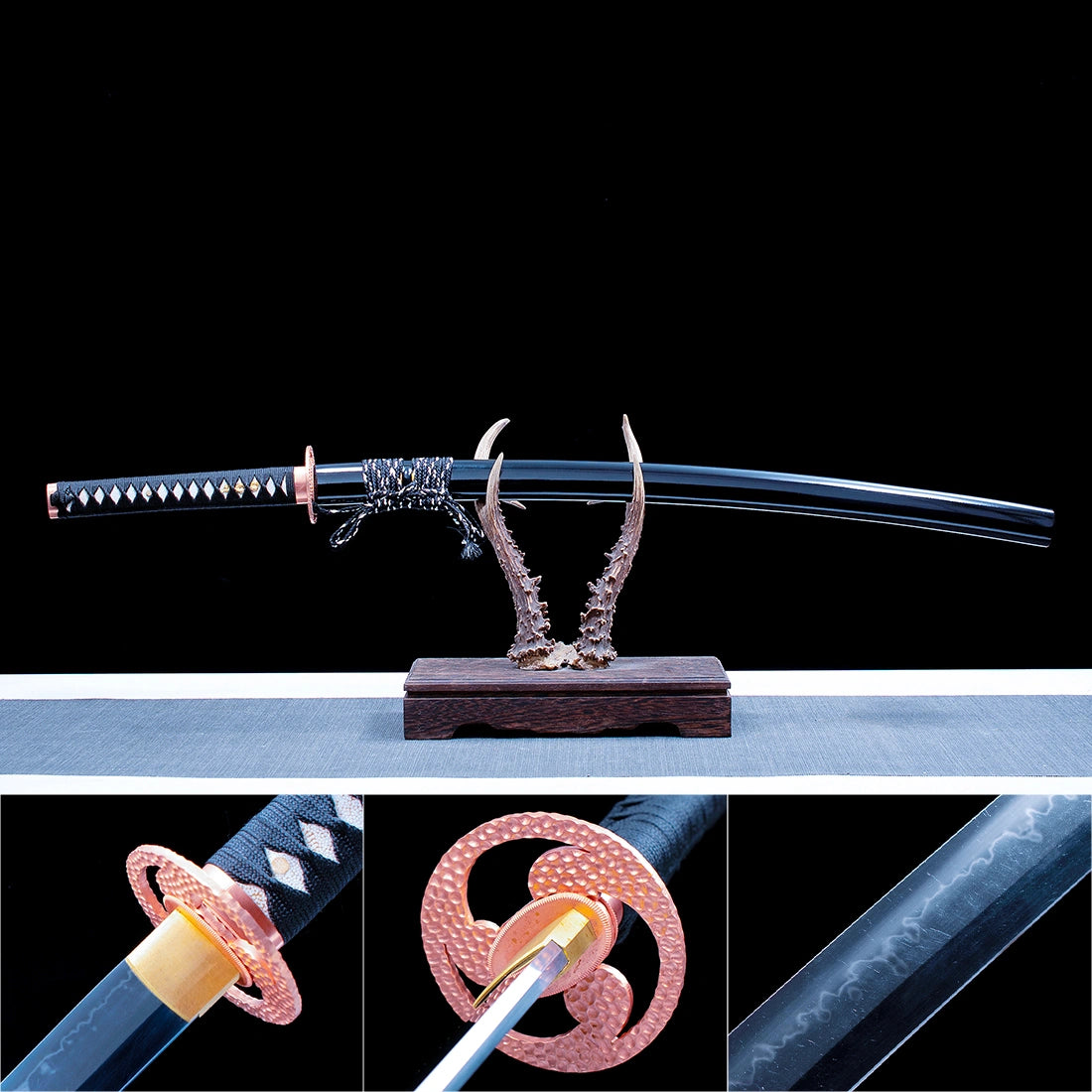

- Katana (刀 or かたな): In modern parlance, both in Japan and internationally, "katana" is often used as a catch-all term for any Japanese sword. Technically, however, it refers to a specific type: a curved, single-edged sword with a blade length (nagasa) of greater than 2 shaku (approximately 60.6 cm or 23.9 inches), worn thrust through the obi (sash) with the cutting edge facing up. This mounting style is called uchi-gatana and became standard for primary swords from the Muromachi period (approx. 1392–1573) onward.

2. Typological Classification by Form and Function

A professional classification is based on the physical attributes of the blade itself.

A. By Blade Length (Nagasa):

This is the primary method of categorization, established by the Edo period's strict sword laws.

- Tachi (太刀): The precursor to the katana. A long, deeply curved sword designed for use by cavalry, worn suspended from the belt with the cutting edge down. Blade length is typically over 2 shaku. The signature (mei) of the smith is usually on the side of the tang (nakago) that faces outward when worn (the omote side).

- Katana (刀): As defined above. The signature, if present, is on the side of the tang that faces the body when worn (the ura side).

- Wakizashi (脇差): A "companion sword" with a blade between 1 and 2 shaku (approx. 30.3 cm to 60.6 cm). Worn alongside the katana by the samurai class as a pair called daishō (大小, "big-little"). It was used for indoor combat and, ritualistically, for seppuku.

- Tantō (短刀): A dagger or knife with a blade shorter than 1 shaku (under ~30.3 cm). Served as a utility blade and a weapon for very close-quarters combat.

- Naginata (長刀) / Nagamaki (長巻): While not straight swords, they feature sword-like blades mounted on long poles. The naginata has a deeply curved blade, while the nagamaki has a long hilt wrapped like a katana's to facilitate swinging.

B. By Historical Period and Construction Method:

- Jōkotō (上古刀): "Ancient swords." Blades made before the mid-Heian period (circa 794). They are straight (chokutō), often with a double-edged (kiriha-zukuri) profile, showing strong influence from Chinese and Korean designs.

- Kotō (古刀): "Old swords." Blades made from the mid-Heian period (circa 900) until the Keichō era (1596-1615). This period represents the zenith of the swordsmith's art. Blades are characterized by profound curvature, dramatic temper patterns (hamon), and often a majestic, functional beauty. Smiths from the Kamakura period are among the most revered.

- Shintō (新刀): "New swords." Blades made from the Keichō era (1596-1615) through the end of the Edo period (1781). Swords became straighter, wider, and thicker, reflecting a shift from battlefield use to dueling and civilian wear. The hamon often became more flamboyant and decorative.

- Shinshintō (新新刀): "New new swords." Blades made from the late Edo period (circa 1781-1876) onwards. This was a revivalist movement that sought to return to the superior qualities and aesthetics of the kotō period, often with mixed success.

- Gendaitō (現代刀): "Modern swords." Blades made from 1876 to the present day. This includes swords made by living National Treasure (Ningen Kokuhō) smiths who continue the traditional craft.

- Shōwatō (昭和刀): A non-traditional subset of 20th-century blades. These are non-traditionally made swords (often using mill steel or modern methods) produced for military officers between 1926 and 1945. They are not considered Nihontō by purists and are often referred to derogatorily as gunto (military swords) or "showato."

3. The Anatomy of a Japanese Sword: A Metallurgical Marvel

A professional description is incomplete without understanding its construction. A Nihontō is not a simple piece of sharpened steel; it is a composite structure of different types of steel, meticulously forged and heat-treated.

- Steel (Tamahagane): The raw material is tamahagane (玉鋼), "jewel steel," produced in a traditional clay tatara smelting furnace. This raw bloomery steel is sorted by carbon content: high-carbon (hard, brittle) and low-carbon (softer, tougher).

- Lamination: The smith forges the core of the blade (shingane) from softer, low-carbon steel for flexibility and shock absorption. The outer skin (kawagane) is made of hard, high-carbon steel that can be sharpened to a razor's edge. These are forge-welded together.

- Folding: The steel is repeatedly folded and forge-welded, not primarily to create layers (a common misconception) but to homogenize the steel, evenly distributing carbon and burning out impurities. The resulting layers (jihada) create a unique grain pattern visible on the polished surface.

- Differential Hardening (Yaki-ire): This is the most critical and revered step. The blade is coated with a layer of refractory clay (tsuchioki); a thin layer is applied along the edge and a thicker layer on the back and sides. The blade is then heated to a critical temperature and quenched in water.The thinly-coated edge cools almost instantly, transforming into a super-hard microstructure called martensite.The thickly-coated spine and core cool much more slowly, forming softer, tougher pearlite.This process creates the supremely hard, sharp cutting edge backed by a flexible, shock-absorbing spine. It also physically forces the blade to curve and creates the hamon (刃文), the temper line, which is the visible boundary between these two microstructures. The hamon is the smith's signature and is studied in minute detail for authentication.

4. Distinction Between Blade and Mounting

A crucial professional distinction is between the blade itself and its furniture.

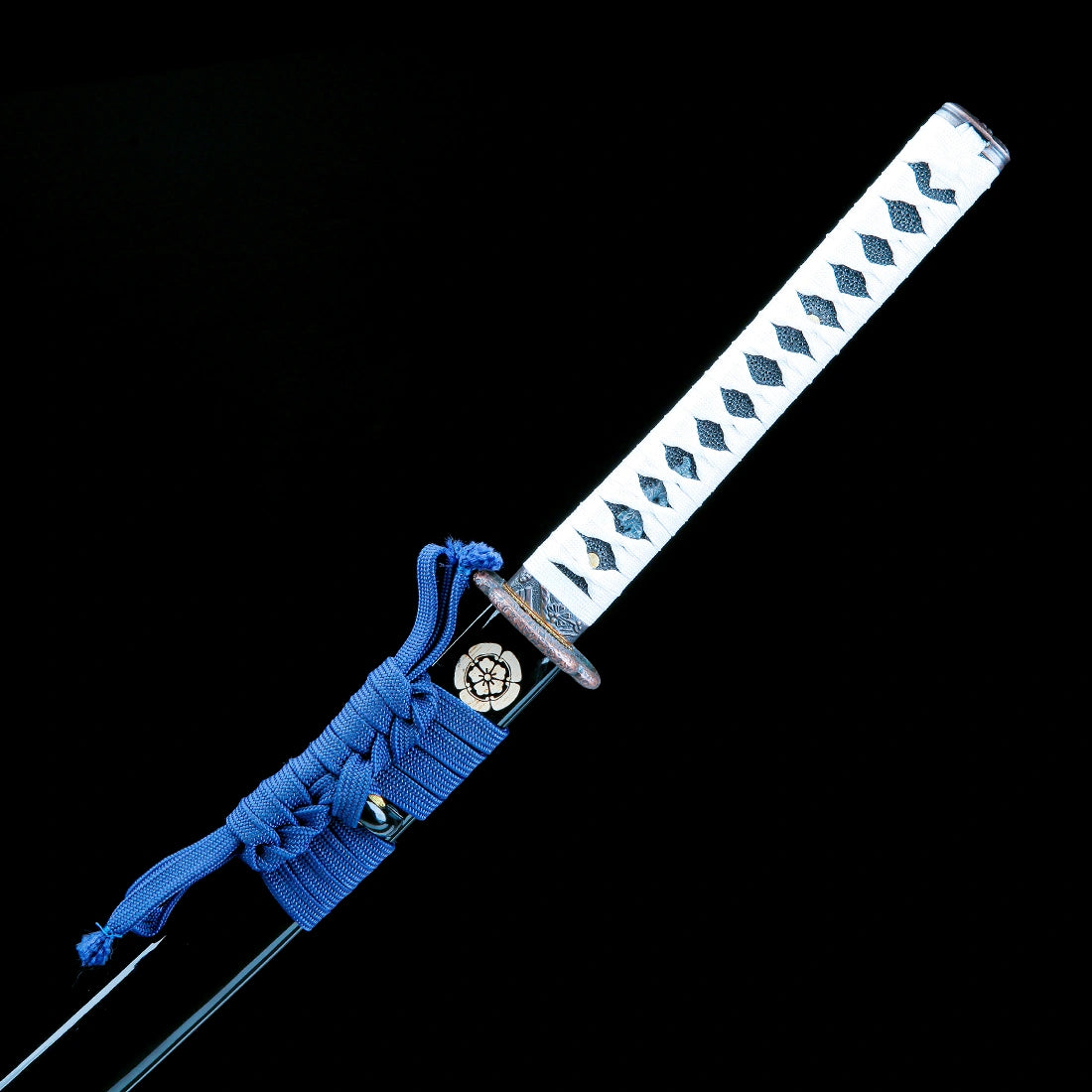

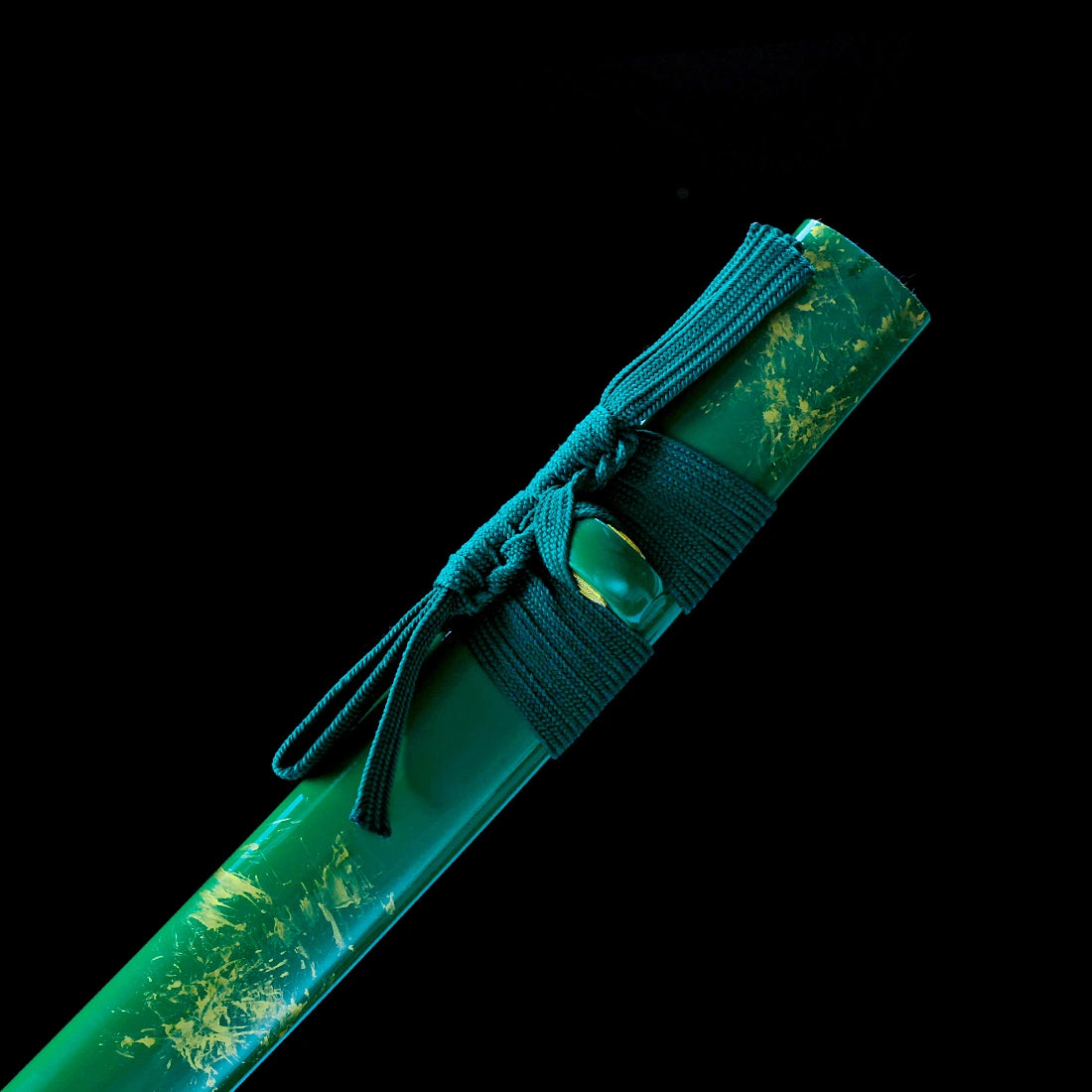

- Shirasaya (白鞘): A "white scabbard." A plain, undecorated wooden storage mount made of honoki magnolia wood. It protects the blade from humidity and allows for easy handling and study. In shirasaya, the object is purely the blade.

- Koshirae (拵え): The functional, often ornate, mounting meant for wear. It includes the scabbard (saya), hilt (tsuka), handguard (tsuba), and all other fittings (fuchikashira, menuki, etc.). A single blade could have multiple koshirae for different occasions.

Conclusion: The Definitive Answer

Therefore, the most precise and professional answer is:

The Japanese sword is generically and correctly termed Nihontō (日本刀). However, specific types are defined by their length and mounting, the most famous being the Katana (刀), a long sword worn edge-up in the belt. The term encompasses a complex family of blades—including Tachi, Wakizashi, and Tantō—whose defining characteristics are a single-edged, curved geometry and a sophisticated laminated construction method featuring differential heat treatment, which produces an exceptionally hard cutting edge and a unique temper line pattern known as the Hamon.

What are the three samurai swords called?

What are the three samurai swords called?

The Professional Explanation of the Samurai's Three Swords: The Daishō and Beyond

The concept of the "three samurai swords" is more accurately described as the standard armament of a samurai, which evolved over time. It primarily refers to the paired long and short sword combination called the Daishō (大小), with the addition of a third, more personal blade. This set was not just a weapon arsenal; it was the ultimate symbol of a samurai's social rank, personal honor, and warrior spirit.

It is crucial to understand that these are classifications based on blade length, and each category contains immense variety in style, school, and smith.

1. The Daishō (大小): The "Big-Little" Pair

The Daishō is the cornerstone of a samurai's identity during the Edo period (1603-1868). The right to wear both a long and a short sword was an exclusive privilege of the samurai class, enforced by law.

A. The Long Sword: The Katana (刀) or Tachi (太刀)

This is the "big" (大, dai) part of the pair, the samurai's primary weapon for open combat.

- Definition: A curved, single-edged blade with a length (nagasa) exceeding 2 Shaku (approximately 60.6 cm or 23.9 inches).

- Technical Distinction:Katana (刀): The most commonly associated sword from the Muromachi period (1336–1573) onward. It was worn thrust through the obi (sash) with the cutting edge up, allowing for a single, swift drawing motion (iaijutsu) to execute a cut. The signature (mei) of the smith, when present, is carved on the side of the tang (nakago) that faces the body when worn.Tachi (太刀): The earlier form of the long sword, predominant in the Kotō ("old sword") period before circa 1596. It is generally more curved and longer than a typical katana. It was designed for cavalry use and worn suspended from the belt with the cutting edge down. The signature is on the outward-facing side of the tang. A samurai from an ancient lineage might wear his family's heirloom tachi as part of his daishō even in the Edo period.

- Construction: As detailed previously, the katana/tachi is a marvel of metallurgy. Its core is constructed from multiple steels: a super-hard high-carbon steel edge forge-welded to a tougher, more flexible low-carbon steel spine and core. The differential hardening process (yaki-ire) creates the distinct hamon (temper line) and grants the blade its legendary combination of sharpness and resilience.

B. The Companion Sword: The Wakizashi (脇差)

This is the "small" (小, shō) part of the pair.

- Definition: A blade with a length between 1 and 2 Shaku (approximately 30.3 cm to 60.6 cm). Its mounting is typically similar in style and quality to its longer companion, creating a cohesive set.

- Function and Symbolism:Practical Use: It was used for close-quarters combat indoors where drawing a long katana was impractical, for beheading defeated opponents, and for ritual suicide (seppuku or harakiri).Social Significance: A samurai was never without his wakizashi. He would remove his long katana when entering a home or a lord's castle but would keep his wakizashi at his side at all times, signifying that he was always armed and always a warrior.Personal Armament: The wakizashi was considered so personal that it was often used by a second (kaishakunin) to perform the mercy stroke during seppuku.

2. The Third Sword: The Tantō (短刀)

The tantō completes the trio. It is the most personal and versatile blade.

- Definition: A dagger or knife with a blade length shorter than 1 Shaku (under ~30.3 cm).

- Function:Utility and Last Resort: It served as a general-purpose utility tool and an absolute last-ditch weapon in grappling situations (yoroi kumiuchi).Symbolic and Ceremonial Use: Exquisitely made tantō were carried by both samurai men and women of the noble class. For a samurai woman, it was a weapon for self-defense and, if necessary, to take her own life (by severing the jugular vein, a ritual known as jigai) to avoid capture and dishonor. They were also common as protective talismans and gifts.

- Variants: While the straight-bladed tantō is classic, a common variation is the Aikuchi (合口), which has no handguard (tsuba), allowing the hilt (tsuka) and the scabbard (saya) to meet (ai) perfectly. This made for a very discreet and sleek mounting.

Context and Evolution

It is important to note that this three-sword set was the ideal standard for a well-equipped samurai, particularly during the peaceful Edo period. In earlier, more war-torn periods like the Sengoku Jidai (Warring States Period, 1467-1590), a samurai on the battlefield might carry a tachi and a tantō, or later a katana and a wakizashi, often supplemented by other weapons like the naginata (polearm) or a bow. The full daishō pairing became a standardized symbol of status as society moved from constant warfare to a more policed, bureaucratic peace.

Conclusion: The Definitive Answer

The "three samurai swords" refer to the traditional armament that symbolized a samurai's soul and status:

- The Long Sword (Daitō): Typically the Katana (or heirloom Tachi), the primary weapon and soul of the warrior.

- The Companion Sword (Shōtō): The Wakizashi, the constant companion that represented the samurai's unwavering readiness and honor.

- The Dagger (Tantō): The Tantō, a multi-purpose tool and deeply personal weapon for utility, close combat, and ritual.

Together, the long and short sword form the Daishō (大小), the defining symbol of the samurai class, while the tantō completes the practical and symbolic trilogy of blades that were an integral part of a samurai's life and identity.

What are the 5 Japanese swords?

What are the 5 Japanese swords?

The Tenka Goken (天下五剣): A Professional Analysis of Japan's Five Supreme Swords

The Tenka Goken (天下五剣) translates to "The Five Swords Under Heaven." This is not a formal classification like those based on blade length, but rather a cultural and historical designation bestowed upon five specific, legendary blades. They are revered not merely as weapons, but as peerless works of art, symbols of political and spiritual power, and embodiments of the pinnacle of the Japanese swordsmith's craft. Each is designated as a National Treasure (国宝, Kokuhō) and is carefully preserved in museums or Shinto shrines, rarely displayed to the public.

The concept of the Tenka Goken is believed to have originated during the Muromachi period (1336–1573), a time when the ruling Ashikaga shoguns amassed and appraised great art and swords, solidifying their cultural authority.

1. Dōjigiri Yasutsuna (童子切安綱)

- Smith: Attributed to Hōki-no-Kuni Yasutsuna (伯耆国の安綱), active in the early Heian period (c. 10th-11th century). He is one of the earliest and most legendary smiths in Japanese history.

- Name Meaning: "Demon-Cutter Yasutsuna." The name derives from its most famous feat: slaying the fearsome demon Shuten-dōji (酒呑童子) who terrorized the region around Kyoto.

- Significance: Often considered the preeminent blade among the five (Tenka Ichi, 天下一, "Foremost Under Heaven"). It represents the very genesis of the Japanese sword as we know it—the transition from straight blades (chokutō) to the iconic curved tachi form. Its existence is a testament to the advanced skill of the earliest master smiths.

- Current Status: Designated a National Treasure. Held in the Tokyo National Museum.

- Characteristics: A magnificent tachi with a pronounced curvature. Its hamon (temper line) is a dynamic and powerful suguha (straight) pattern with subtle fluctuations, a hallmark of the ancient Yamato and Ko-Bizen traditions.

2. Mikazuki Munechika (三日月宗近)

- Smith: Sanjō Munechika (三条宗近), active in the mid-Heian period (c. 987–1094). He was the founder of the renowned Sanjō school in Kyoto.

- Name Meaning: "Crescent Moon Munechika." The name comes from the distinct, crescent-moon-shaped (mikazuki) patterns in the nie crystals within the hamon.

- Significance: Celebrated as one of the most aesthetically beautiful swords ever created. It is the quintessential representation of the graceful and refined artistry of the Heian court nobility. Its flawless proportions and breathtaking hamon make it an object of pure artistic perfection.

- Current Status: Designated a National Treasure. Held in the Tokyo National Museum.

- Characteristics: A tachi of exceptional elegance. Its hamon is a spectacular suguha based on the ko-midare (small irregular) pattern, glittering with bright nie (martensite crystals). The crescent moon shapes (mikazuki) within this line are its unique fingerprint.

3. Onimaru Kunitsuna (鬼丸国綱)

- Smith: Awataguchi Kunitsuna (粟田口国綱) of the Kyōto-based Awataguchi school, active in the Kamakura period (13th century).

- Name Meaning: "Demon Circle Kunitsuna." Legend states that the guardian spirit of the sword appeared in a dream to the regent Hōjō Tokimasa in the form of a small monk, who then used the sword to cut down a demon (oni) that was tormenting him. The sword then fell and cut a standing lantern (andon) shaped like a demon's head, hence "demon circle."

- Significance: This sword became one of the Three Imperial Regalia of the Shogunate (将軍家伝来の三つ物), passed down through the Ashikaga, Toyotomi, and Tokugawa shogunates. It is a symbol of political legitimacy and shogunal authority.

- Current Status: Designated a National Treasure. Held by the Imperial Household Agency.

- Characteristics: A powerful and majestic tachi from the golden age of sword smithing. It exhibits a magnificent hamon, likely a complex choji-midare (clove-shaped pattern) typical of the renowned Awataguchi school, known for its exquisite craftsmanship and beautiful jihada (grain pattern).

4. Ōdenta Mitsuyo (大典太光世)

- Smith: Miike Mitsuyo (三池光世) of the Miike school in Chikugo province, active in the late Heian or early Kamakura period.

- Name Meaning: "The Great Denta Mitsuyo." "Denta" (典太) is an alternate reading for "Mitsuyo," and "Ō" (大) means "Great," signifying its supreme status among his works.

- Significance: Like the Onimaru, it was one of the Three Imperial Regalia of the Shogunate. It was famously owned by the great warlord Maeda Toshiie and passed down as the most prized treasure of the Maeda clan of Kaga domain. It was believed to have potent healing properties and was once used in a ritual to try to cure a shogun's illness.

- Current Status: Designated a National Treasure. Held at the Maeda Ikutokkai Foundation.

- Characteristics: Known for its rugged, utilitarian, and immensely powerful construction. It has a wide body, a thick kasane (spine), and a short nakago (tang), giving it a stout and fearsome appearance. Its hamon is a bold and bright suguha (straight pattern), projecting an aura of raw, unstoppable force.

5. Juzumaru Tsunetsugu (数珠丸恒次)

- Smith: Attributed to Aoe Tsunetsugu (青江恒次) of the Bizen-based Aoe school, active in the Kamakura period (13th century).

- Name Meaning: "Rosary Circle Tsunetsugu." The name comes from the Buddhist rosary (juzu) that the Buddhist reformer Nichiren is said to have hung on its hilt when he carried the sword, not as a weapon, but as a symbolic instrument to "cut through earthly desires and illusion."

- Significance: This sword holds a unique position as a sacred religious object. Unlike the others, its fame stems not from cutting demons or being a symbol of political power, but from its association with Nichiren and its role in Buddhist practice. It represents the spiritual dimension of the sword.

- Current Status: Designated a National Treasure. Held at Honkō-ji temple in Amagasaki.

- Characteristics: A classic tachi from the Aoe school, which is renowned for its exceptional sharpness and superb technical quality. Aoe blades are famous for their elegant chōji-midare hamon and a distinct, vibrant jihada known as aoe-hada.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Tenka Goken

The Tenka Goken are more than just sharp blades; they are cultural keystones. Collectively, they represent:

- The Evolution of Form: From the ancient Dōjigiri to the Kamakura-period masterpieces, they chart the technical and artistic evolution of the Japanese sword.

- Diverse Symbolism: They embody raw power (Dōjigiri, Ōdenta), artistic perfection (Mikazuki), political authority (Onimaru), and spiritual sanctity (Juzumaru).

- Historical Witnesses: Each blade has been passed down through generations, owned by shoguns, warlords, and saints, silently witnessing over a millennium of Japanese history.

- Metallurgical Perfection: They represent the absolute highest achievement in the complex art of Japanese sword forging, a combination of sophisticated metallurgy, spiritual dedication, and sublime aesthetics that remains unsurpassed.

Is it samurai or katana?

Is it samurai or katana?

A Professional Disambiguation: Samurai vs. Katana

The question "Is it samurai or katana?" highlights a fundamental point of confusion. These two terms are not interchangeable; they refer to entirely different concepts within the field of Japanese history and material culture. To use them correctly is to understand the critical distinction between a human warrior class and an inanimate object wielded by them.

This is a classic case of confusing the agent (the actor) with the tool (the instrument). To put it in simple terms: a samurai is a person, and a katana is a type of sword that person carried.

Part 1: The Samurai (侍) - The Human Element

The term Samurai (侍) is a noun referring to a member of a specific, elite socio-military class in pre-modern Japan.

- Etymology and Meaning: The word derives from the verb saburau (侍う), meaning "to serve" or "to attend to a person of nobility." This etymology is crucial—it defines the samurai's primary role as a retainer, a servant to a lord (daimyō) or the shogun. A more formal, Chinese-derived term for this class was bushi (武士), meaning "martial gentleman" or "warrior."

- Historical and Social Context: The samurai emerged as a powerful land-owning class in the Heian period (794-1185) and became the ruling military class from the Kamakura period (1185–1333) until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Their existence was governed by a strict ethical code, later idealized as Bushidō (武士道, "the way of the warrior"), which emphasized virtues like loyalty, honor, self-discipline, and martial mastery.

- Professional Definition: A samurai was defined by:Lineage: Birth into the samurai caste.Political Role: Service to a lord in a military or administrative capacity.Social Privilege: The right to bear two swords (the daishō, 大小) and the right to execute a commoner who disrespected them (kiri-sute gomen, 斬捨御免) under certain conditions in the Edo period.A Way of Life: Their entire identity was built around the profession of arms, governance, and the cultivation of martial and literary arts.

In summary: A samurai was a person, a member of Japan's hereditary warrior aristocracy.

Part 2: The Katana (刀) - The Material Object

The term Katana (刀) is a noun referring to a specific type of Japanese sword. It is an object, a tool, and a work of art.

- Etymology and Meaning: The word katana is a generic term for "sword" or "blade" in Japanese, but in a historical and professional context, it has a precise definition.

- Technical Classification: As defined by the Edo period's strict regulations, a katana is a curved, single-edged blade with a length (nagasa) of greater than 2 Shaku (approximately 60.6 cm or 23.9 inches). Its key distinguishing feature from the earlier tachi (太刀) was its method of wear: it was thrust through the obi (sash) with the cutting edge facing up (uchi-gatana). This allowed for a seamless, rapid drawing motion to execute a cut (iaijutsu).

- Cultural and Symbolic Significance: While a tool, the katana was far more than a simple weapon. Due to the exquisite craftsmanship required to forge it using traditional methods (folding, clay tempering, etc.), it was considered the "soul of the samurai." It was a sacred object, a status symbol, a family heirloom, and a embodiment of the wielder's honor. However, it is critical to remember that this symbolism is derivative—the sword gains its cultural importance from its association with the samurai class who wielded it.

In summary: A katana is a physical object, a type of long sword that was the primary sidearm of the samurai class.

Part 3: The Relationship and Common Conflation

The confusion between the two terms arises from their deeply intertwined history and cultural representation.

- The Primary Armament: The katana was the definitive weapon of the samurai, especially from the Muromachi period (1336–1573) onward. The paired daishō (katana and wakizashi) was the legal and social right exclusive to the samurai class.

- Symbolic Metonymy: In art, literature, and film, the katana is often used as a metonym—a object used to represent the entire concept of the samurai. For example, a film scene focusing on a katana being drawn is a visual shorthand for the samurai's readiness for combat, his skill, and his honor.

- Modern Pop Culture: Global popular culture, through movies, anime, and video games, has often simplified this relationship, using "katana" as a catchy, exotic word to invoke the entire image of a Japanese warrior. This has led to the erroneous use of "a katana" to mean "a samurai warrior."

Professional Conclusion: Correct Usage

To answer the question "Is it samurai or katana?" definitively:

- You would say, "The samurai drew his katana." (A person drew an object).

- You would not say, "A katana drew his sword." (An object cannot perform a human action).

- You would say, "The samurai class was abolished in 1876." (Referring to people).

- You would not say, "The katana class was abolished." (Referring to objects).

- You would say, "This katana was forged by the master smith Masamune." (Referring to an object).

- You would not say, "This samurai was forged by Masamune." (Referring to a person).

Final Answer: They are distinct concepts. Samurai refers to the warrior-class individual. Katana refers to the specific type of sword they carried. The katana is an inseparable attribute of the samurai, but it is not synonymous with the samurai himself.

What is a ninja sword called?

What is a ninja sword called?

The "Ninja Sword": A Professional Demystification

The popular concept of a distinct "ninja sword" is, from a historical and academic perspective, largely a modern invention heavily influenced by 20th-century cinema, manga, and popular culture. The professional answer requires dismanting the myth and examining the reality of the tools used by historical operatives known as shinobi or ninja.

The Popular Myth: The Ninjato (忍者刀) or Shinobigatana (忍刀)

The sword most commonly imagined is called a Ninjatō (忍者刀) or Shinobigatana (忍刀). Its stereotypical features include:

- A straight, or nearly straight, blade: Contrary to the curved katana.

- A square or rectangular guard (tsuba): Often depicted as large and simple.

- A long, oversized scabbard (saya): Said to be used for storing other tools, breathing underwater, or as a blowgun.

- A shorter, simpler blade: For practicality in confined spaces.

Important Note: There is no period evidence (e.g., surviving examples, historical manuals, detailed descriptions from the Sengoku or Edo periods) that confirms the existence of a standardized, mass-produced sword fitting this exact description. This iconic image was solidified in the popular imagination by post-WWII media.

The Historical Reality: Tools of the Shinobi

Historical operatives (shinobi, 忍び) did not use a single, specialized "sword." Instead, they adapted and used existing tools and weapons, prioritizing function, disguise, and practicality over standardized form. The primary bladed tool would have been a modified version of a common sword or a utilitarian blade.

1. The Katana or Wakizashi in Disguise

A shinobi operating in enemy territory would often be disguised. Carrying a unique, easily identifiable sword would immediately compromise their cover. A professional operative would more likely carry:

- A standard, unremarkable katana or wakizashi to blend in with samurai or commoners.

- A sword with its mounting (koshirae) deliberately aged or rusted to appear old and less valuable, avoiding attention.

- A blade with a dull edge (yaiba), as their weapon was more likely used for silent stabbing, prying, or utility than for formal, sharp-edged dueling.

2. The Practical and Multi-Purpose Tool: The Shinobizue (忍び杖)

This was far more common and practical than a specialized sword. A shinobizue ("shinobi staff") was a seemingly ordinary walking staff, cane, or pilgrim's staff that concealed a blade, chain, or other weapon inside. This was the ultimate tool for infiltration, as it was a completely innocuous object that could be carried openly without suspicion.

3. The Utilitarian Short Blade: A Modified Wakizashi or Chokutō

For close-quarters combat, silent entry, and utility work, a shinobi would likely use a short, sturdy blade. The closest historical equivalents would be:

- A stout Wakizashi (脇差): Its shorter length was ideal for use in tight spaces, inside buildings, or for silent killing. It could be worn on the back for easier draw while climbing.

- A Chokutō (直刀): An old-style straight sword. While largely obsolete on the battlefield by the shinobi's heyday (Sengoku period), a straight blade would be more effective for thrusting into gaps in armor or through shoji screens and would be easier to manufacture or obtain cheaply. However, they would have been antiques, not a newly designed "ninja sword."

4. The Tool for Breaching: The Kunai (苦無)

It is critical to distinguish this from a sword. The Kunai was not a primary weapon but a multi-purpose tool and impromptu weapon. Originally a masonry trowel or prybar, it was:

- Used for: Prying open doors, windows, and fences; digging holes; hammering pitons for climbing; as a handhold for ropes; and, as a last resort, for stabbing or throwing.

- Design: It was a unsharpened or minimally sharpened piece of forged iron with a ring pommel for attaching a rope. Its modern depiction as a sharp throwing star is a significant exaggeration.

Why the Straight Blade Myth Persists

The notion of a straight blade has logical, though speculative, roots that explain its persistence:

- Utility: A straight blade is better for thrusting into armor gaps and is simpler to forge, potentially making it cheaper for an operative who might have to abandon it.

- Concealment: A straight blade could be worn flush against the back, reducing snagging while climbing or moving through dense vegetation.

- Iconography: In modern media, a straight blade provides a clear, instant visual distinction from the samurai's curved katana, quickly signaling to the audience that the character is a ninja.

Professional Conclusion: The Definitive Answer

There is no historical evidence for a standardized weapon called a "ninja sword" or ninjatō. The romanticized image is a modern construct.

Historically, a shinobi would have used:

- A standard, disguised katana or wakizashi for blending in.

- A shinobizue (concealed-cane sword) for infiltration.

- A kunai (prybar/tool) for breaching and utility.

- Various other tools (shuriken, metsubushi, etc.) for specific missions.

The core principle of shinobi equipment was adaptation and practicality. They used whatever tool best suited the mission, always prioritizing stealth and deception over standardized, honor-bound warfare. Therefore, the most accurate professional answer is that a "ninja sword" is a modern pop-culture term for which no definitive historical artifact exists. The reality was far more nuanced, practical, and diverse.

What is an uchigatana?

What is an uchigatana?

The Uchigatana (打刀): A Professional Analysis of the Blade that Defined an Era

The term Uchigatana (打刀) is one of the most significant yet frequently misunderstood terms in the study of Japanese arms. It does not refer to a specific shape or school of blade, but rather to a method of wear and a historical classification that marks a pivotal evolution in Japanese warfare, culture, and society. It is the direct precursor and formal term for what is now universally known as the Katana (刀).

1. Etymology and Literal Meaning

The term Uchigatana is composed of two elements:

- Uchi (打): This verb means "to strike," "to hit," or "to beat." In this context, it implies a swift, striking motion.

- Gatana (刀): The rendaku (voiced) form of katana, meaning "sword" or "single-edged blade."

Thus, Uchigatana translates most accurately to "striking sword" or "sword for striking." This name directly describes its revolutionary use: a weapon designed to be drawn and cut in a single, fluid, and rapid motion.

2. The Technical and Historical Definition: A Revolution in Wear

The paramount defining characteristic of an uchigatana is not its blade geometry but how it is worn.

- The Predecessor: The Tachi (太刀)

Before the rise of the uchigatana, the dominant long sword was the tachi. It was characterized by:Wear: Suspended edge-down from the belt on two hangers (ashi).Purpose: Optimized for use by mounted cavalry. The downward orientation facilitated drawing while on horseback to make sweeping, downward cuts against foot soldiers.Curvature: Typically had a deeper curvature (sori), often centered in the blade's middle (koshi-zori), which was ideal for drawing and cutting from a saddle.Signature (Mei): The smith's signature was carved on the side of the tang (nakago) that faced outward when worn (the omote side). - The Innovation: The Uchigatana (打刀)

The uchigatana emerged during the late Kamakura (1185–1333) and particularly the Muromachi period (1336–1573), a time of widespread civil war (the Sengoku Jidai, or Warring States period). Its key feature was:Wear: Thrust directly through the obi (sash) or belt, with the cutting edge facing up.Purpose: Optimized for foot combat and rapid engagement. This mounting style allowed the wielder to draw the sword and slash in one uninterrupted, lightning-fast motion. This technique became formalized as iaijutsu (居合術) and later iaidō (居合道).Signature (Mei): The smith's signature was carved on the side of the tang that faced the body when worn (the ura side). This is a crucial point of differentiation from the tachi.

3. Blade Characteristics and Evolution

While the mounting style is the true defining feature, the shift in combat needs influenced the blade's physical attributes over time.

- Early Uchigatana (Mid-Kamakura to Nanbokuchō periods): These were often converted tachi blades that were shortened (suriage) and re-mounted for the new edge-up style. They often retained a relatively deep curvature.

- Sengoku Period Uchigatana: This was the heyday of the uchigatana. As warfare became constant and large-scale armies of foot soldiers (ashigaru) were raised, swords needed to be produced in greater numbers and be more effective against infantry. Blades became:Shorter and Straighter: Less curvature (often saki-zori, curvature towards the tip) for more effective thrusting and closer-quarters fighting.Wider and Thicker: More robust to withstand the rigors of battlefield use and to deliver more powerful cuts, sometimes through lightweight armor.Less Aesthetically Refined: The focus was on functional efficiency over artistic perfection, leading to a style known as Kazuuchi-mono (批量物), or "mass-produced items." However, many high-quality blades were still made for high-ranking officers.

4. The Uchigatana's Legacy: The Birth of the Katana

By the end of the Muromachi period, the uchigatana had completely supplanted the tachi as the primary battlefield sidearm for samurai. With the establishment of the peaceful Edo period (1603–1868), the term Katana (刀) gradually became the standard and more elegant term for this now-ubiquitous weapon.

- The Daishō (大小): The uchigatana/katana became one half of the daishō pair, worn alongside the wakizashi. This pairing became the exclusive symbol of the samurai class, codified in law.

- From Battlefield to Dueling Hall: In peacetime, the sword's role shifted from a battlefield tool to a dueling weapon, a status symbol, and the "soul of the samurai." The uchigatana's design, perfected for a rapid draw, made it ideal for the formalized duels and martial arts (koryū bujutsu) of the Edo period.

Professional Conclusion: The Definitive Answer

An Uchigatana (打刀) is not merely a type of sword but represents a critical evolutionary stage in Japanese sword history. It is specifically defined as:

A long, curved, single-edged sword designed to be worn thrust through the obi (sash) with the cutting edge facing upwards, facilitating a rapid-draw and cut technique. It emerged during the Muromachi period as a response to the changing nature of warfare, shifting from cavalry combat to mass infantry battles. It is the direct functional and historical predecessor of the weapon that would later, in the Edo period, become universally known as the Katana.

Therefore, while all modern katana are descended from the uchigatana tradition, the term uchigatana itself carries a specific historical and technical connotation that is vital for professional-level classification and understanding.

What is a large katana called?

What is a large katana called?

The "Large Katana": A Professional Examination of Oversized Japanese Blades

The question of a "large katana" requires precise terminology, as the Japanese sword classification system is based on specific measurements, intended use, and historical context. There is no single official term for a "large katana," but rather several correct terms depending on the exact nature of the blade. The common pop-culture notion of an oversized katana is often a modern invention.

1. The Standard Baseline: Defining the Katana

To understand "large," we must first define the standard. A Katana (刀) is formally defined as a curved, single-edged blade with a length (nagasa) of 2 Shaku or greater (approximately 60.6 cm or 23.9 inches), designed to be worn thrust through the obi with the edge facing up.

Any blade significantly exceeding these dimensions falls into specialized categories.

2. The Primary Category: Ōdachi (大太刀) / Nodachi (野太刀)

This is the most accurate and historical term for a genuinely large battlefield sword.

- Ōdachi (大太刀): Literally "Great Big Sword." This is the most formal and technical term.

- Nodachi (野太刀): Literally "Field Sword," implying its use on the open battlefield as opposed to confined spaces or daily wear.

Characteristics:

- Size: Typically, a blade length (nagasa) of 3 Shaku (~90.9 cm / 35.8 in) or more. Many extant examples are over 100 cm (39 inches) in blade length alone, with total lengths exceeding 150 cm (59 inches).

- Function: These were primarily field weapons used during the Nanbokuchō (1336–1392) and Sengoku (1467–1600) periods.Anti-Cavalry: Their immense length and weight made them effective for striking down cavalrymen and horses.Frontline Shock Weapon: Wielded by elite soldiers on the front lines to break enemy formations, exploiting their incredible reach and intimidating presence.Ceremonial Offerings: Some extraordinarily large ōdachi were never intended for combat but were forged as offerings to Shinto shrines to demonstrate a smith's skill or to invoke divine protection.

Practical Challenges:

- Weight and Balance: An ōdachi is incredibly heavy and cumbersome. It required exceptional strength and skill to wield effectively.

- Drawing: It was impossible to draw from the waist in a conventional manner. Techniques involved wearing it on the back or carrying it over the shoulder. Often, a companion would help draw it.

- Storage and Transport: Its size made it impractical for daily wear. During the peaceful Edo period, the ōdachi fell almost completely out of practical use due to strict sword laws and a lack of large-scale warfare.

3. The Comparative Category: The Long Katana (長刀 - Chōtō?)

While not a formal historical classification, a blade that is noticeably longer than a standard katana but does not reach the proportions of an ōdachi might be referred to descriptively.

- For example, a katana with a nagasa of approximately 75-80 cm (~2.5 shaku) could be called a nagasa no nagai katana (長さの長い刀) – "a katana with a long blade."

- It's crucial to note that Japanese sword classification is based on strict shaku measurements. A blade over 2 shaku is a katana/daitō, regardless of how long it is within that range. The term ōkatana (大刀) is ambiguous, as it can be a synonym for katana itself or read as ōdachi.

4. The Common Misconception: The Zanbatō (斬馬刀)

- Zanbatō (斬馬刀): Literally "Horse-Cutting Sword" or "Horse-Slaying Sword."

- Reality: This is primarily a fictional and modern term. While the name appears in some very old Chinese and Japanese texts describing a type of polearm or glaive, its contemporary association with an impossibly large, often wide-bladed anime/video-game sword is a 20th-century invention.

- There are no known historical examples of a Japanese sword designed specifically for cutting horses that matches the fantastical modern image. The functional role of cutting down cavalry was fulfilled by the ōdachi/nodachi, as well as by polearms like the naginata (長刀) and nagamaki (長巻).

5. Why So Large? The Metallurgical Marvel

The creation of an ōdachi represents the absolute pinnacle of a swordsmith's technical skill.

- Forging Challenges: Creating a billet of tamahagane steel large and homogeneous enough for an ōdachi was immensely difficult. The folding (kitae) and forge-welding process had to be perfectly controlled over a much larger area to prevent fatal flaws.

- Differential Hardening (Yaki-ire): This was the most perilous step. Heating a blade of that size evenly to the critical temperature (~800°C) and then plunging it into the water quench tank required a team of smiths and perfect timing. The risk of cracking, warping, or an imperfect hamon (temper line) was extremely high.

- Polishing: Sharpening and polishing an ōdachi requires special setups and techniques, often needing two people to handle the blade on the polishing stone.

Professional Conclusion

A truly large katana is not simply a big version of a standard sword. It is a specialized weapon with a specific name and purpose.

The correct historical term for a very large Japanese sword is Ōdachi (大太刀) or Nodachi (野太刀). These were functional, albeit rare, battlefield weapons that represented the zenith of samurai swordsmithing technology during periods of intense warfare.

The popular image of a massive "horse-cutting sword" (Zanbatō) is a modern, fictional construct with little basis in historical reality. When classifying a Japanese blade, precision in terminology—based on measurements, mounting, and historical use—is paramount. The "large katana" exists firmly within the defined category of the ōdachi.