FAQs

How much is a real samurai sword?

How much is a real samurai sword?

The Valuation of samurai sword: A Professional Market Analysis

The question "How much is a real samurai sword?" is akin to asking "How much is a house?" The price range is extraordinarily vast, from a few thousand dollars to well over a million, entirely dependent on a complex matrix of objective and subjective factors. A "real" sword, or samurai sword (日本刀), is valued as both a weapon and a work of art, and its price reflects this dual nature.

It is critical to first define "real." In a professional context, this refers to a blade that is:

- Made in Japan using traditional methods (laminated steel, clay tempering).

- Primarily forged and finished by hand.

- Often, but not always, of a certain age (typically pre-20th century).

This excludes modern, non-traditionally made replicas, which have a separate and much lower market value.

The Four Pillars of Valuation

The price of a Nihontō is determined by four primary pillars, each with its own complexities.

Pillar 1: Provenance & Paperwork (由来と鑑定書 - Yurai to Kanteisho)

This is the most critical factor for establishing authenticity and value. Paperwork from official Japanese organizations is the equivalent of a verifiable provenance and artist's signature in the Western art world.

- NBTHK (日本美術刀剣保存協会 - Society for the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords): The most common and respected authority for certification.Hozon (保存) Certificate: ("Worthy of Preservation") The base-level certification. It authenticates the blade as a true Nihontō and assigns it to a specific school or smith. A blade with Hozon papers has passed a rigorous examination. Price Impact: Adds a significant premium (often $2,000-$5,000+ to the value of an otherwise unpapered blade) as it guarantees authenticity.Tokubetsu Hozon (特別保存) Certificate: ("Especially Worthy of Preservation") A higher level of certification for finer quality works.Jūyō (重要) Certificate: ("Important Work") A major step up. Blades designated as Jūyō are considered nationally important cultural artifacts. The process is extremely selective. Price Impact: Prices typically enter the $30,000+ range and can go far higher.Tokubetsu Jūyō (特別重要) Certificate: ("Especially Important") The highest level from the NBTHK. Extremely rare and reserved for masterworks of supreme importance. Price Impact: Prices are typically in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

- Jūyō Bunkazai (重要文化財): Designation as an "Important Cultural Property" by the Japanese government. This is a national treasure status. Price Impact: Effectively priceless; sale is rare and would be in the millions of dollars.

A blade with no paperwork is a major risk and will be valued significantly lower, as its attribution is speculative.

Pillar 2: The Smith & School (刀工 - Tōkō)

The reputation of the smith is the single greatest determinant of value.

- Legendary Masters (e.g., Masamune, Muramasa, Sadamune): Their works are virtually never on the open market. If one were to appear, it would be an auction event with an estimated price well exceeding $1,000,000.

- Top-Tier Rated Smiths (e.g., Rai Kunimitsu, Awataguchi Yoshimitsu, Ichimonji School): Blades by famous smiths from the Ko-To (old sword) period, especially those designated Jūyō or above. Price Range: $100,000 - $500,000+

- Important Provincial Smiths (e.g., Bizen Osafune, Mino Seki, Sōshū Masters): Excellent quality blades from renowned schools and smiths. Price Range: $25,000 - $100,000

- Competent, Papered Smiths: Good quality, authentic blades from identifiable and skilled but less famous smiths. This is a very common category for collectors. Price Range: $8,000 - $25,000

- Mumei (無名 - "No Signature") but Papered: High-quality blades where the signature has been lost (e.g., due to shortening). Value is based on the quality of the workmanship and the NBTHK's attribution to a school or period. Price Range: $4,000 - $15,000

Pillar 3: Condition & Quality (状態 - Jōtai)

Two blades by the same smith can have vastly different values based on their state of preservation.

- Polish: A professional, high-quality polish (togi) is essential to reveal the blade's activity (hataraki). A poor polish or one that is near the end of its life (too many polishes have worn away the steel) drastically reduces value. A new polish can cost $3,000 - $10,000+ itself.

- Flaws (Kizu - 傷): The presence of fatal flaws like cracks (hagire), welding flaws (ware), or serious rust pits (fukure) can render a blade virtually worthless to a serious collector. Minor, stable flaws will decrease value but may be acceptable.

- Activity (Hataraki - 働き): The aesthetic qualities within the steel and temper line: the presence of nie (crystals), nioi (a misty line), kinsuji (lightning-like streaks), chikei (curving lines), etc. More pronounced and interesting activity increases value.

- Shape (Sugata - 姿): The overall form and proportions of the blade. A bold, healthy shape from its period is valued. A blade that has been severely altered from its original shape (e.g., greatly shortened) loses value.

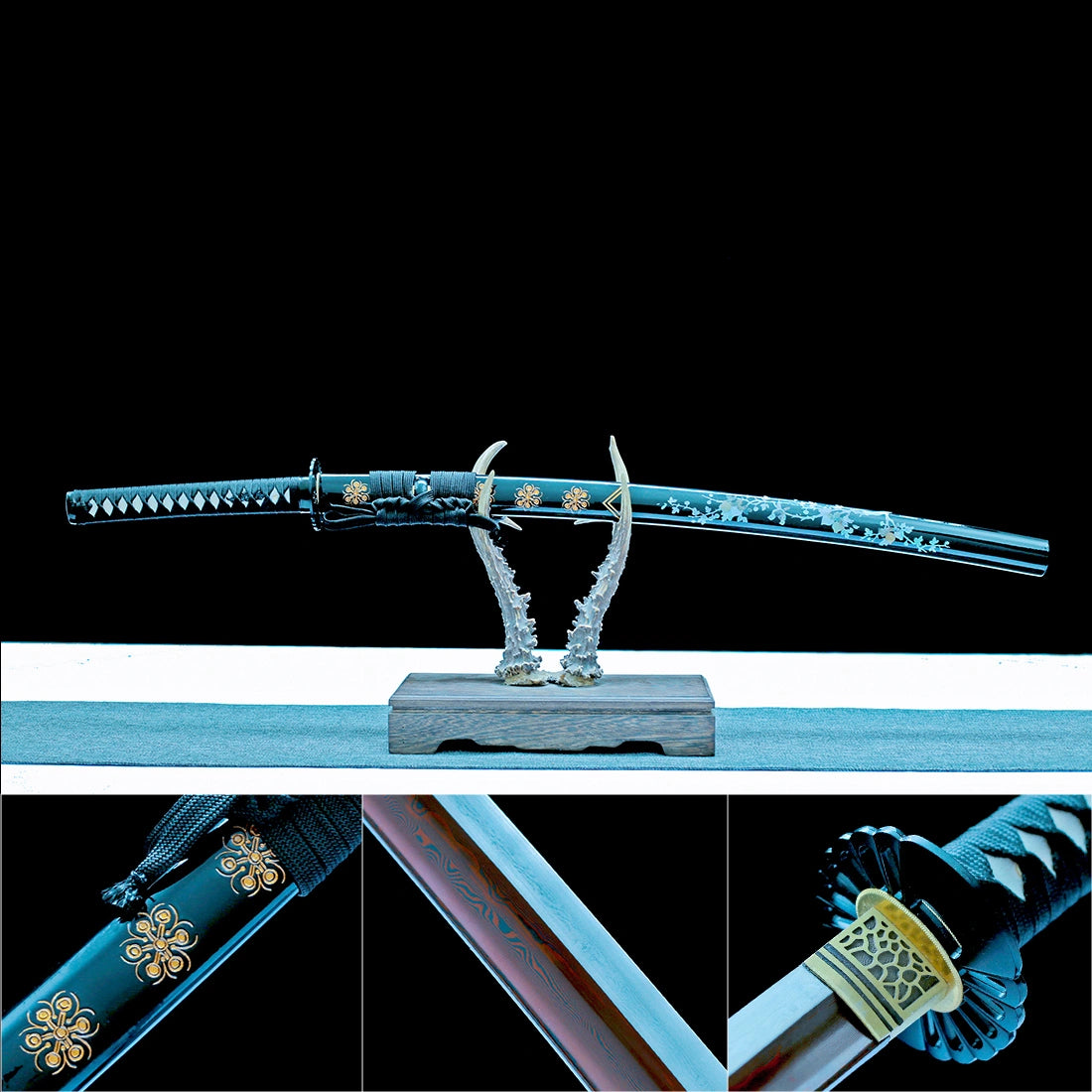

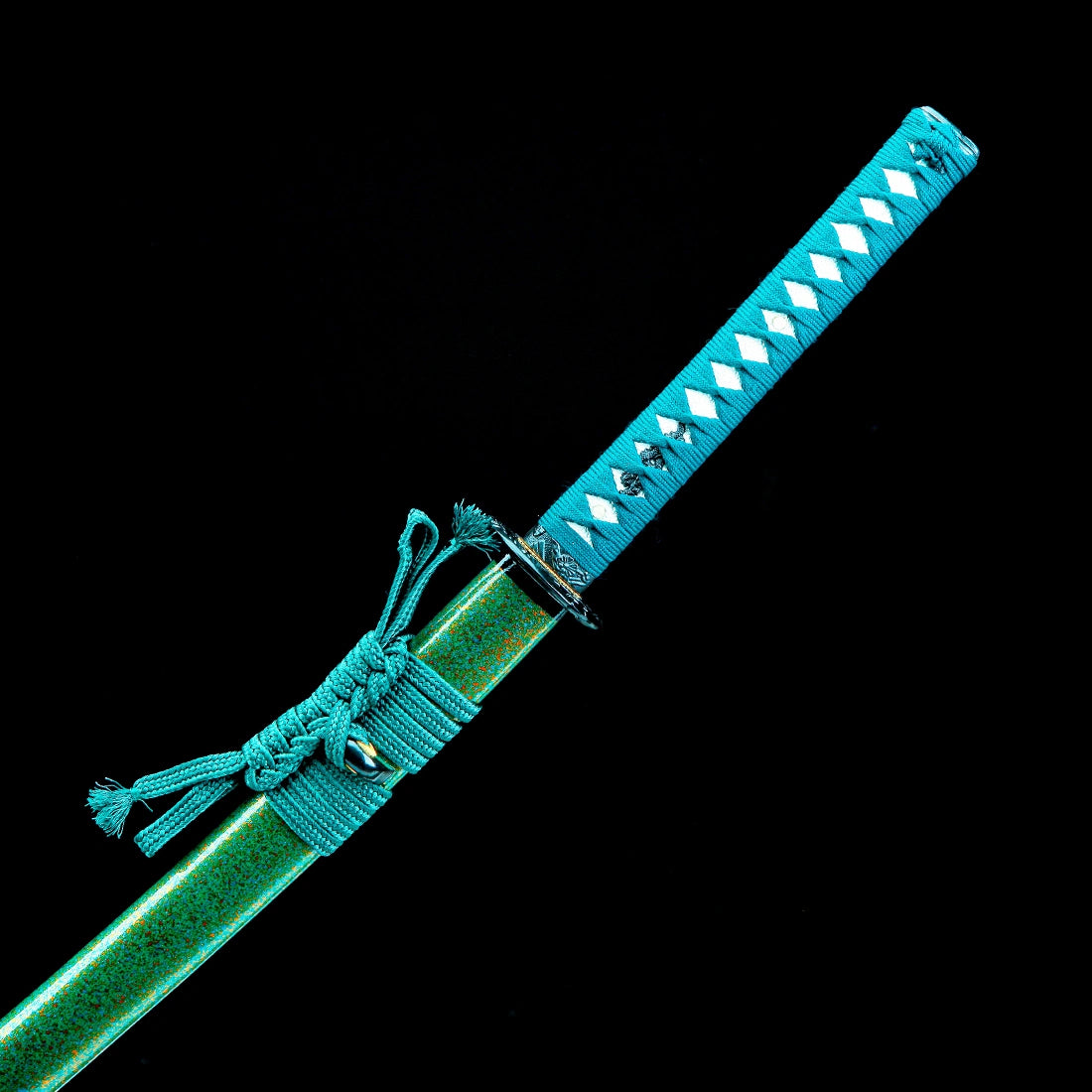

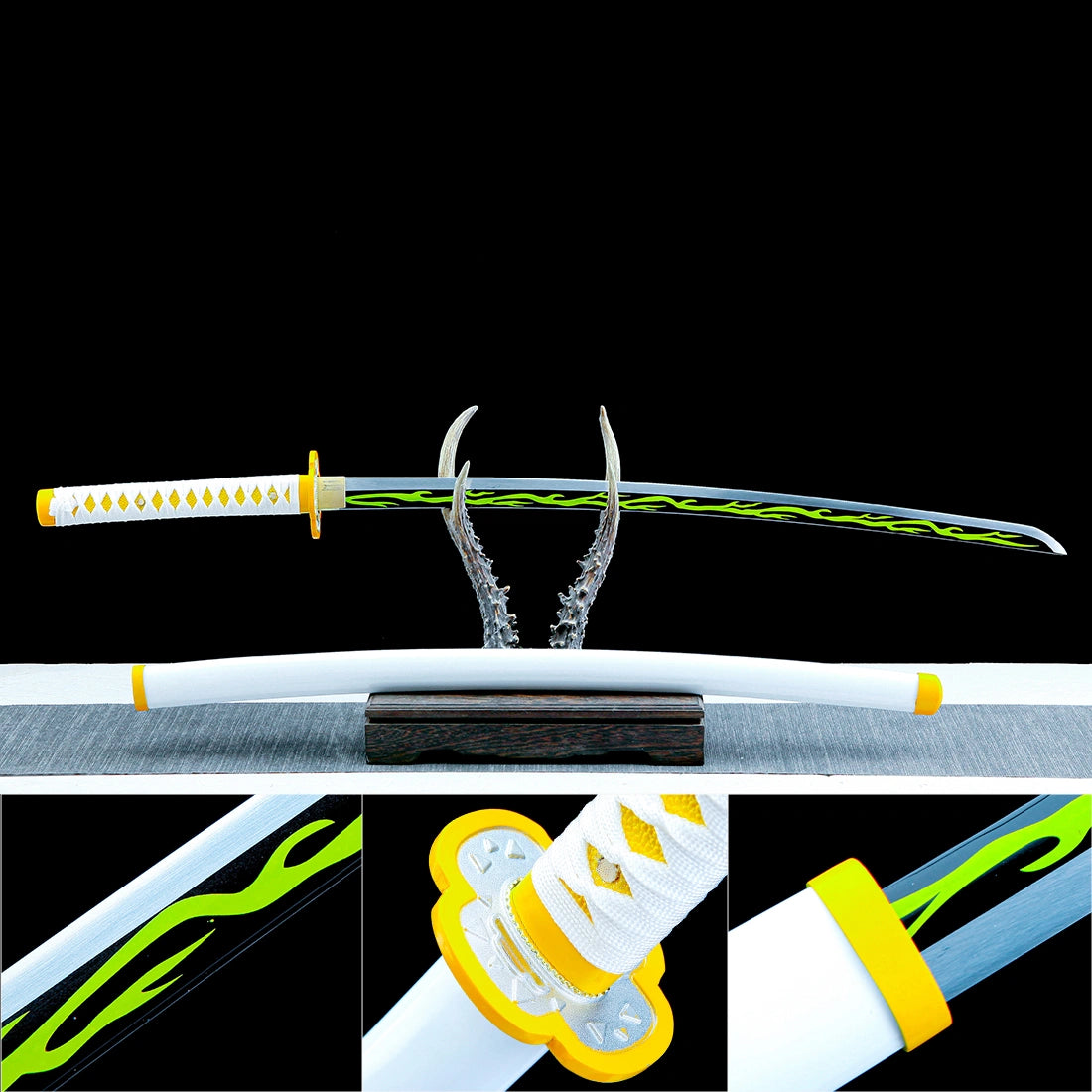

Pillar 4: Mountings (拵 - Koshirae) & Fittings (装具 - Sōgu)

The sword's furniture can be a collection unto itself and is valued separately from the blade.

- Original Mountings (Koshirae): A complete, period-correct, and undamaged mounting can add significant value, especially if it is of high artistic quality itself. Can add $2,000 - $20,000+

- Storage Mountings (Shirasaya - 白鞘): Most blades are sold in plain wood shirasaya for conservation. This is standard and does not typically add a major premium.

- Fittings (Tosōgu - 刀装具): A signed tsuba (guard) by a famous master like Nobuie or Natsuo can be worth $5,000 - $50,000+ on its own. High-quality fuchi-kashira (pommel/collar), menuki (grip ornaments), and kozuka (utility knife handle) also add considerable value.

Additional Critical Costs

- Import/Export Fees: Legal export from Japan requires a permit. Importing into another country (e.g., the USA, UK) may involve customs duties and requires compliance with local laws (e.g., in the UK, items over 100 years old are exempt from restriction).

- Insurance: Insuring a valuable art object requires specialized appraisal and comes with an annual cost.

- Maintenance: Costs for conservation, new shirasaya, and eventually repolishing must be factored into long-term ownership.

Conclusion

There is no single price for a real samurai sword. The market is a hierarchy:

- $3,000 - $8,000: The entry point for verifiable, papered antiques, typically smaller blades or those with minor imperfections.

- $8,000 - $25,000: The range for a good quality, papered katana by a competent smith—a true collector's piece.

- $25,000+: The domain of high-grade, investment-quality art pieces where factors of smith fame, artistic merit, and perfect condition command premium prices.

Ultimately, a samurai sword is valued on its merits as a unique piece of functional art. Its price is a direct reflection of its authenticity, artistry, condition, and historical significance, each layer verified and certified by a rigorous traditional system.

What is a samurai sword called?

What is a samurai sword called?

The Taxonomy of the Japanese Sword: A Professional Discourse

The term "samurai sword" is a modern, non-specific colloquialism. Within the specialized field of Nihontō (日本刀) studies, the correct terminology is precise, reflecting the blade's historical period, physical dimensions, method of wear, and functional purpose. There is no single answer, but rather a hierarchy of classification.

1. The Overarching Term: Nihontō (日本刀)

The most accurate and professional generic term is Nihontō (日本刀), which translates to "Japanese sword." This term specifically denotes a blade that is:

- Traditionally forged using multiple steels (tamahagane) through methods of folding, welding, and clay tempering.

- Curved and single-edged (though early exceptions exist).

- Culturally significant, embodying the aesthetic and spiritual values of the Japanese people.

This term distinguishes these art objects from foreign blades (Yōtō, 洋刀) or modern, non-traditionally made replicas.

2. Classification by Blade Length (Nagasa - 長さ)

The primary method of categorization, established during the peaceful Edo period (1603-1868), is the precise measurement of the blade from tip (kissaki) to the back of the notch (machi) where the tang (nakago) begins.

- Tachi (太刀) & Katana (刀): Both are "long swords" (daitō, 大刀) with a blade length exceeding 2 Shaku (approximately 60.6 cm or 23.9 inches). Their distinction lies not in length, but in mounting and wear (detailed below).

- Wakizashi (脇差): The "companion sword" with a blade length between 1 and 2 Shaku (approx. 30.3 cm to 60.6 cm). Worn alongside the long sword by the samurai class to form the daishō (大小, "big-little") pair, the ultimate symbol of their status.

- Tantō (短刀): A dagger or knife with a blade length shorter than 1 Shaku (under ~30.3 cm). Served as a utility tool and a weapon for extreme close quarters or ritual suicide (seppuku).

3. Classification by Historical Period & Mounting

This is where the crucial distinction between the two most famous long swords, the Tachi and the Katana, is made.

A. Tachi (太刀)

- Period: Predominant from the Heian (794-1185) through the early Muromachi period (1336–1573). The weapon of the classic mounted samurai.

- Mounting & Wear: Designed for cavalry use. It was worn suspended from the belt with the cutting edge down. This allowed for an efficient downward draw to strike at foot soldiers while on horseback.

- Aesthetics: Typically has a deeper, more pronounced curvature (sori), often centered in the middle of the blade (koshi-zori).

- Signature (Mei): The smith's signature is carved on the side of the tang that faces outward when worn (the omote side).

B. Katana (刀)

- Period: Rose to prominence in the mid-Muromachi period ( Sengoku Jidai, or Warring States period) and became the standard thereafter.

- Mounting & Wear: A product of changing warfare tactics, emphasizing foot combat. It was worn thrust through the obi (sash) with the cutting edge facing up. This facilitated an incredibly rapid drawing motion (iaijutsu) where drawing and cutting became one fluid action. This method of wear is specifically called Uchigatana (打刀, "striking sword").

- Aesthetics: Generally has a shallower curvature, sometimes closer to the tip (saki-zori), and a more robust build for close-quarters infantry combat.

- Signature (Mei): The signature is on the side of the tang that faces the body when worn (the ura side).

Therefore, a katana is technically a type of mounting (uchigatana) for a long sword blade. In modern parlance, "katana" has become the catch-all term for this style.

4. Classification by Historical Era of Manufacture

Connoisseurs further classify blades by the era in which they were forged, each with distinct characteristics:

- Kotō (古刀 - "Old Swords"): Blades made circa 900–1596. Represent the zenith of the art, characterized by profound elegance, dramatic temper patterns (hamon), and often a majestic, functional beauty. Highly prized by collectors.

- Shintō (新刀 - "New Swords"): Blades made circa 1596–1780. Generally straighter, wider, and more uniform. The hamon often became more flamboyant and decorative.

- Shinshintō (新新刀 - "New New Swords"): Blades made circa 1780–1876. A revivalist movement attempting to recapture the quality and aesthetics of the Kotō period.

- Gendaitō (現代刀 - "Modern Swords"): Blades made from 1876 to the present by smiths who continue the traditional craft.

- Shōwatō (昭和刀 - "Shōwa Era Swords"): Non-traditionally made blades (using mill steel, oil quenching) produced for military officers between 1926-1945. They are not considered art-quality Nihontō by purists.

Professional Conclusion: The Definitive Answer

There is no single term for a "samurai sword." The correct terminology depends on context:

- For the paired set symbolizing the samurai: Daishō (大小), comprising the long sword (daitō - either a tachi or katana) and the companion short sword (wakizashi).

- For the standard long sword worn edge-up from the Muromachi period onward: Katana (刀) or, more technically, Uchigatana (打刀).

- For the earlier long sword worn edge-down by classical samurai: Tachi (太刀).

- As a generic term for all traditionally-made Japanese blades: Nihontō (日本刀).

To use the term "samurai sword" is a generalization. To use the specific terms—Tachi, Katana, Wakizashi, Tantō—is to demonstrate an understanding of their distinct historical functions, forms, and cultural significance. The soul of the samurai was not in a single weapon, but in the mastery of an entire arsenal, each piece with its own name and purpose.

Can you legally own a samurai sword?

Can you legally own a samurai sword?

The Legality of Owning a Samurai Sword: A Global and Technical Analysis

The question of legality is complex and varies dramatically by jurisdiction. There is no single, global answer. Ownership hinges on critical distinctions between the sword's type, age, cultural status, and method of manufacture, as well as the specific laws of the country, state, or even city in which you reside.

1. The Foundational Distinction: Art vs. Weapon

The legal status of a Japanese sword almost universally depends on its classification as either:

- A Cultural Art Object / Antique: This applies to traditionally made, historically significant blades.

- A Modern Weapon / replica: This applies to non-traditionally made, modern reproductions.

The key factors determining this classification are:

- Traditional Manufacture (Nihontō): A blade hand-forged in Japan using traditional methods (laminated tamahagane steel, clay tempering). These are considered cultural artifacts.

- Age: In many jurisdictions, items over a certain age (e.g., 100 years) are automatically classified as antiques, which often exempts them from weapons laws.

- Method of Manufacture: Modern, factory-made swords using monosteel (e.g., 1060 carbon steel), machine grinding, and oil quenching are typically classified as weapons or "replicas" and face much stricter regulations.

2. Jurisdiction-Specific Legislation (Overview)

A. Japan: The Source Country

Japan has the most stringent and culturally-specific laws designed to protect its national heritage.

- The Cultural Property Law: Traditionally made Japanese swords (Nihontō) are considered important cultural assets. It is illegal to export them without permission.

- The Sword and Firearm Possession Law: To legally own a Nihontō in Japan, a citizen must:Obtain a permit (Tōken Juyō Shōmeisho - 刀剣所持証明書) from the Agency for Cultural Affairs.The sword must be registered with the government (Tōrōku - 登録), and a registration card (Tōrōku Shōmeisho) is issued for each blade. This card must stay with the sword forever.The ownership permit is based on a background check, proving the owner has a legitimate interest (collecting, martial arts) and secure storage facilities.

- Export Control: Exporting a registered Nihontō requires an additional export permit from the Agency for Cultural Affairs. This is to prevent the loss of cultural treasures. Without this permit, the sword will be confiscated by Japanese customs.

B. United Kingdom: A Highly Restrictive Model

The UK has some of the strictest weapons laws in the world, but they make a clear distinction for antiques.

- The Criminal Justice Act 1988 (Offensive Weapons) Order 1988: This law made it illegal to manufacture, sell, hire, or import curved swords with a blade over 50cm (~19.7 inches), with very specific exceptions.

- The Exemption: The law provides an exemption for "hand-made Japanese samurai swords" that are "made in Japan before 1954" or "made at a later date by a traditionally trained swordsmith".

- In Practice: This means:You can legally own and import a traditionally made, antique katana (Nihontō).You can legally own a modern, traditionally made katana from a licensed Japanese smith (e.g., a gendaitō).It is illegal to import, buy, or sell modern, non-traditionally made "samurai swords" (e.g., Chinese-made replicas, wall hangers). Ownership of such items is also likely to be illegal.The burden of proof is on the owner to provide evidence of traditional manufacture (e.g., paperwork from the NBTHK, proof of smith).

C. United States: A State-by-State Patchwork

The U.S. has no federal law banning samurai swords, but numerous states and cities have their own ordinances.

- Federal Law: No restriction on ownership or importation of antique or modern swords for adults.

- State/Local Laws: This is where it becomes complex. Laws vary wildly:Most States: No restrictions (e.g., Texas, Florida, Ohio). Ownership of any type is legal.Restrictive States/Cities: Some jurisdictions ban specific types.California: prohibits the importation and sale of "undetectable knives" and certain swords, but ownership is generally legal. Some cities have stricter codes.New York State: Law is generally permissive, but New York City has a specific administrative code (§ 10-133) that bans the possession of any "katana" in public without a valid permit. Keeping one at home is legal.Age Restrictions: Many states prohibit the sale of swords to minors.

D. Canada, Australia, and the EU

- Canada: Generally permissive. Swords are not classified as prohibited weapons. Ownership is legal, though carrying them in public could lead to charges of possessing a weapon for a dangerous purpose.

- Australia: Laws are strict and vary by state. Importing requires a permit from police. In most states, ownership requires a genuine reason (e.g., collecting, membership in a martial arts society). Registration and secure storage are often mandatory.

- European Union: Like the US, there is no single EU-wide law. Countries like Germany require a weapons license (Waffenschein) for ownership, which is difficult to obtain. France and Italy are more permissive, often classifying traditional swords as cultural objects. Ireland has very restrictive laws similar to the UK.

3. The Critical Role of Paperwork and Provenance

For international trade and legal proof, documentation is everything.

- NBTHK Papers: A certification from the Nihon Bijutsu Tōken Hozon Kyōkai (日本美術刀剣保存協会 - Society for the Preservation of Japanese Art Swords) (e.g., Hozon, Tokubetsu Hozon, Jūyō) is the gold standard. It authenticates the blade as a cultural art object, identifies its maker and period, and drastically simplifies customs procedures.

- Japanese Registration Card (Tōrōku Shōmeisho): This is the official government document that must accompany any sword exported legally from Japan. It is definitive proof of the sword's legal status and cultural value.

- Export Permit: The official permit from the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs allowing the sword to leave the country.

Without these documents, a valuable antique can be seized by customs authorities as a potential cultural property violation or an illegal weapon.

Professional Conclusion: A Step-by-Step Guide

To determine if you can legally own a specific "samurai sword":

- Identify the Sword: Is it a traditionally-made Nihontō (antique or modern) or a non-traditional modern replica? Paperwork is key here.

- Research Your Local Jurisdiction: Do not rely on internet folklore. Consult the actual legislation for your country, state/province, and city. When in doubt, contact a local law enforcement agency or a specialized lawyer.

- For Nihontō (Cultural Art Object):In most of the world: Ownership is legal, but you may need to prove its status as an art object (via paperwork) for importation.In highly restrictive places (e.g., UK): Ownership is legal only for these traditionally-made pieces. You must ensure it meets the specific legal criteria.

- For Modern Replicas:In permissive jurisdictions (e.g., most of US): Ownership is generally legal.In restrictive jurisdictions (e.g., UK, Australia, NYC): Ownership is likely illegal. These items are classified as controlled weapons.

Final Answer: Yes, you can often legally own a real, traditionally-made samurai sword (Nihontō), but it is highly dependent on your specific location and the sword's certification. Ownership of modern replicas is far more heavily restricted. The legality is not based on the sword itself, but on its classification under your local law. Always prioritize rigorous research and proper documentation.

Can a katana cut through bones?

Can a katana cut through bones?

The Katana and Bone: A Biomechanical and Metallurgical Analysis

The question of whether a katana can cut through bone is not a simple yes or no. The answer is a qualified yes, a katana is fully capable of cutting through bone, but the outcome is dependent on a complex interplay of physics, blade geometry, cutting technique, and the specific nature of the bone itself. It is not the mystical, effortless feat often depicted in popular culture.

1. The Physics of Cutting: Force, Pressure, and Energy

Cutting is fundamentally an application of physics. To cut through any material, a blade must exert pressure greater than the material's ultimate tensile or shear strength.

- Pressure = Force / Area: The katana's design maximizes pressure by concentrating tremendous force onto an extremely fine edge (the ha). The curvature (sori) of the blade facilitates a drawing motion (hikigiri), which creates a slicing action that dramatically increases the effective cutting distance and application of force, compared to a simple chopping motion.

- Kinetic Energy = 1/2 mass * velocity²: The energy of the cut comes from the mass of the sword and the square of its velocity. A proper cut uses the entire body, not just the arm, to maximize both the speed and the mass behind the swing (incorporating the body's weight and rotation).

2. The Katana's Design: Optimized for Cutting

The katana is the result of centuries of empirical refinement for the purpose of cutting. Its features are perfectly suited to this task:

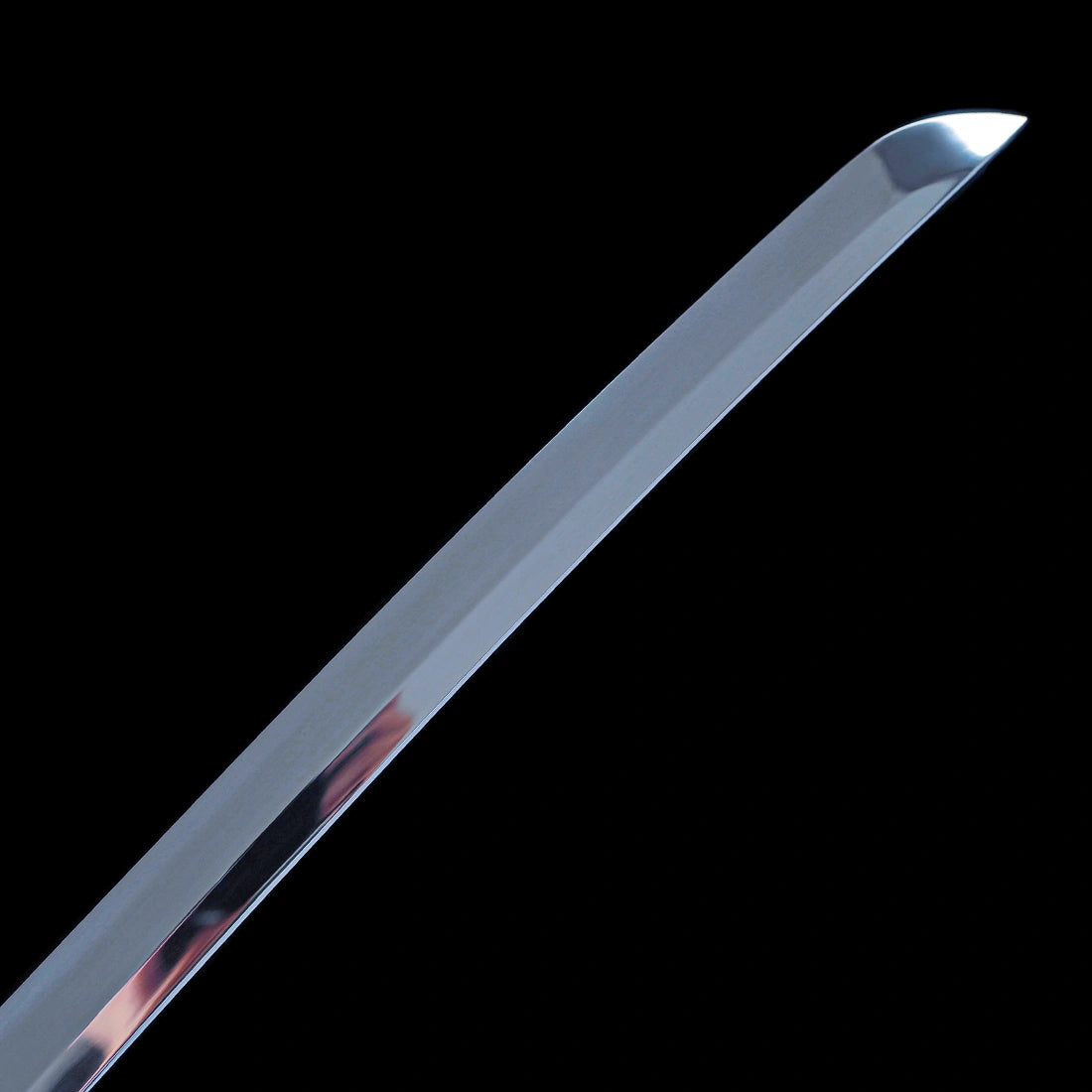

- Differential Hardness (Differential Hardening): The clay tempering process (yaki-ire) creates a blade with a supremely hard, brittle edge (Rockwell C hardness of ~60-65) backed by a softer, tougher spine and core. This allows the edge to achieve and maintain a phenomenal degree of sharpness without the entire blade being so hard that it shatters on impact.

- Blade Geometry: The cross-section of a katana is a complex, subtly convex shape (niku). This geometry provides structural strength behind the edge, preventing it from buckling or rolling upon impact with a hard target like bone.

- The Edge (Ha): A properly polished katana has an edge that is not a simple "V" but a complex, multi-faceted structure that terminates in an almost infinitely fine cutting surface. Under a microscope, a truly sharp katana edge appears as a smooth, continuous arc of steel, allowing it to initiate a cut with minimal resistance.

3. The Nature of Bone: A Formidable Biological Material

Bone is not a uniform material. Its density, thickness, and structure vary greatly throughout the body, which is a critical factor.

- Cortical vs. Cancellous Bone:Cortical Bone (Compact Bone): The hard, dense outer shell of bones. This is the primary barrier to a cut. Its strength is significant. A katana can cut through it, but it requires optimal conditions.Cancellous Bone (Trabecular/Spongy Bone): The less dense, porous inner layer of bones (e.g., in the ends of long bones, the pelvis, skull). It offers much less resistance and is far easier to cut through.

- Bone Size and Shape:Thin/Fla Bones: Bones like the ribs, clavicle, or the bones of the forearm (radius and ulna) can be completely severed by a powerful, well-placed cut.Large/Dense Bones: The femur (thigh bone) and the humerus (upper arm bone) are the largest and densest. Severing these completely is extremely difficult and would require a perfect cut from a very strong wielder. It is more likely that a katana would cut deeply into the bone, causing a massive fracture and debilitating injury, but may not achieve a clean, complete amputation in a single stroke.The Skull: The cranium is a curved, thick shell of cortical bone. A direct, perpendicular strike would likely result in a deep gouge or a fractured skull rather than a clean cleaving. A slicing or drawing cut across a thinner area (like the temples) could potentially penetrate.

4. Historical and Forensic Evidence

- Historical Accounts: Edo-period dissection manuals and texts on sword testing (tameshigiri) occasionally reference cutting through bone. The practice of tameshigiri itself often used cadavers or condemned criminals, and results were recorded on the sword's handle (nakago). Cuts that passed through the pelvis (koshi) or through two bodies at once (nidandō) were considered exemplary and demonstrate the blade's ability to cut through bone.

- Forensic Pathology: Modern forensic studies of sharp-force trauma confirm that swords, including katanas, can and do completely sever limbs and cleave skulls. The wounds show clean cuts with micro-fractures at the edges of the bone, characteristic of a very sharp, heavy implement.

Synthetic Summary: The Conditions for Success

A katana can cut through bone if the following conditions are met:

- A Superbly Sharp Blade: The sharpness of the edge is the single most important factor. A dull blade will crush and splinter bone rather than cut it.

- Proper Cutting Technique (Suburi): The cut must be a drawing/slicing motion (hikigiri), not a simple axe chop. This utilizes the blade's geometry to its maximum potential. The angle of incidence must be correct.

- Adequate Force and Velocity: The wielder must generate sufficient kinetic energy through proper body mechanics.

- Target Selection: Cutting through a rib is vastly different from cutting through a femur. The size and density of the bone are paramount.

Professional Conclusion

Can a katana cut through bone? Yes, absolutely. It is an efficient tool designed for that very purpose.

However, the popular image of a katana effortlessly slicing through multiple large bones is hyperbolic. The reality is a transaction of energy:

- The energy required to sever bone is immense. Even with a perfect blade and technique, the cut encounters significant resistance. This resistance transfers force back into the blade and the wielder's hands.

- The blade suffers damage. Impact with bone, even when successful, will cause micro-damage to the fine edge. This is why maintenance (uchiko, oiling) and periodic re-polishing are essential for a functional sword.

- The cut is not "clean" in a biological sense. It would be a violent, traumatic event, involving not just bone but also muscle, tendon, and connective tissue, all of which offer their own resistance.

In essence, the katana is capable of cutting through bone due to its masterful metallurgy and geometry, but it is not a lightsaber. It obeys the laws of physics, and its effectiveness is a testament to the skill of its maker and the skill of its user in harnessing those laws.

Can you buy a katana in Japan and bring it to the US?

Can you buy a katana in Japan and bring it to the US?

Importing a Katana from Japan to the United States: A Comprehensive Legal and Procedural Guide

The short answer is yes, it is absolutely possible to legally purchase a katana in Japan and bring it to the United States, but the process is highly regulated, requires specific documentation, and differs drastically based on the type of sword. Failure to comply with the precise procedures will result in the seizure and destruction of the sword by customs authorities.

The entire process hinges on one critical distinction: is the sword a modern-made replica or an authentic, traditionally-made Nihontō (日本刀)?

Part 1: The Critical Distinction - Defining the "Katana"

A. Authentic Nihontō (Cultural Art Object)

- Definition: A blade hand-forged in Japan by a licensed smith using traditional methods (laminated tamahagane steel, clay tempering, water quenching).

- Age: Can be antique (typically over 100 years old) or modern-made by a contemporary master smith (e.g., a gendaitō 現代刀).

- Legal Status in Japan: Considered an "Art Sword" and a cultural property. It is registered with the Japanese government.

- US Import Status: Generally permissible but requires specific documentation to prove its status. It is imported as a cultural artifact, not a weapon.

B. Modern Replica / Non-Traditional Sword

- Definition: A factory-made sword using modern monosteel (e.g., 1060, 1095 carbon steel), machine grinding, oil quenching, and often mass-produced. This includes "wall hangers" and functional replicas.

- Legal Status in Japan: Not considered a cultural property. Treated as a commodity.

- US Import Status: Strictly regulated by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). It is imported as a weapon and must comply with federal regulations.

Part 2: The Process for Exporting from Japan

This is the most complex and critical step. Japan strictly controls the export of its cultural heritage.

Step 1: Obtain an Export Permit (Yushutsu Kyoka - 輸出許可)

- Issuing Authority: The Agency for Cultural Affairs (Bunkachō - 文化庁) of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT).

- Purpose: This permit is mandatory for the legal export of any sword classified as Nihontō (i.e., any sword with a registration card). It is proof that the Japanese government has approved the removal of this cultural artifact from the country.

- How to Obtain: The seller (e.g., a licensed antique dealer) almost always handles this process for the buyer. It is a complex application that requires:The sword's original Registration Card (Tōrōku Shōmeisho - 登録証明書). This is the legal document that all registered swords in Japan possess.A detailed application form with information about the sword and the exporter.The permit process can take several weeks to months.

Without this permit, Japanese customs will confiscate the sword at the airport.

Step 2: For Non-Traditional Swords (Replicas)

If the sword is a modern replica with no cultural status (no registration card), an export permit is not required. It can be exported as a regular commodity, though you should have a commercial invoice from the seller.

Part 3: The Process for Importing into the United States

U.S. law is generally permissive regarding sword ownership, but customs officials require proof of the item's nature.

For Authentic Nihontō (With Japanese Export Permit)

- Declare the Item: Upon arrival in the U.S., you must declare the sword to CBP officers on your Customs Declaration Form (CBP Form 6059B). Be transparent and state you are importing a "Japanese cultural art sword."

- Present Documentation: You must present the original Japanese Export Permit and the Japanese Registration Card to the CBP officer.

- CBP Review: The officer will inspect the sword and the documentation. The export permit and registration card serve as definitive proof that the item is an art object, not a weapon for import restrictions. This typically results in a smooth clearance.

- No Duty: Antiques (over 100 years old) are generally duty-free. Modern-made gendaitō may be subject to a small duty under Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) code 9307.00.00 ( "Swords, cutlasses, bayonets, lances and similar arms and parts thereof and scabbards and sheaths therefor").

- Shipment: If you are shipping the sword instead of carrying it, you must use a freight forwarder experienced in handling weapons/art. The same documentation must be attached to the shipment and presented to CBP upon its arrival.

For Modern Replicas (Without Japanese Export Permit)

- Regulation by CBP: CBP regulates the importation of "switchblade knives, martial arts weapons, samurai swords, and sword canes" under 19 USC § 1304. The import must comply with federal laws.

- Permissible Import: CBP states that such items are generally permissible for importation if they are not inherently lethal or are only for sporting purposes. However, the burden of proof is on the importer.

- Declaration and Invoice: You must declare the item and present a commercial invoice from the seller in Japan. The invoice should clearly describe the item as a " decorative replica sword" or "martial arts training sword."

- Potential Scrutiny: Without the cultural documentation, the replica is classified as a weapon. While rarely denied entry for an individual item, CBP has the authority to seize it if they deem it prohibited (e.g., if it is a concealed weapon or appears inherently lethal for unlawful purposes).

Part 4: Additional Critical Considerations

- US State and Local Laws: The absence of federal restrictions does not preempt state or local laws. You are responsible for ensuring ownership is legal in your city and state. For example, while ownership is legal in most of the U.S., some cities have restrictions on carrying or transporting blades in public.

- Airline Policies: If carrying the sword personally, you must check it as baggage. It is strictly prohibited in carry-on luggage. You must declare it to the airline at check-in. It must be securely packed in a checked hard-case suitcase. Many airlines have specific policies for transporting weapons; contact them well in advance.

- Endangered Species (CITES): If the sword's fittings (tsuba, menuki) include materials from endangered species (e.g., ivory, whale bone, sea turtle shell), you may need an additional CITES permit from both Japan and the U.S. for export/import. This is a separate and complex process.

Conclusion: The process is designed to protect Japan's cultural heritage. For an authentic katana, the key is securing the Japanese Export Permit, which is your passport for the blade to leave Japan and enter the U.S. legally. For a replica, the process is simpler but comes with less legal certainty upon import. Engaging a knowledgeable dealer in Japan is the most reliable way to ensure full compliance with all international regulations.

Why do samurai carry two swords?

Why do samurai carry two swords?

The Daishō (大小): A Comprehensive Analysis of the Samurai's Two Swords

The practice of carrying two swords, known as the Daishō (大小, literally "big-little"), was not merely a tactical choice but the definitive symbol of the samurai class's identity, social status, and legal privilege during the Edo period (1603-1868). The carrying of two swords represented a complex interplay of practical utility, social law, and profound cultural symbolism.

1. The Composition of the Daishō

The daishō refers to the paired combination of:

- The Long Sword (Daitō - 大刀): This was the primary weapon. In the early periods, this was a Tachi (太刀) worn edge-down. From the mid-Muromachi period onward, it was almost universally a Katana (刀) or Uchigatana (打刀) worn edge-up.

- The Companion Sword (Shōtō - 小刀): This was the secondary weapon, typically a Wakizashi (脇差) with a blade between 1 and 2 shaku (approx. 30.3 cm - 60.6 cm), or occasionally a Tantō (短刀) (dagger).

The pairing was not merely functional; the two swords were often made by the same smith or outfitted with matching fittings (kanagu), such as the guard (tsuba), and handle ornaments (menuki), signifying they were a conceived set.

2. Practical and Tactical Rationale

The two-sword system offered distinct advantages on and off the battlefield:

- Versatility in Combat:Long Sword (Katana/Tachi): Optimized for open battlefield combat, dueling, and any situation where reach and power were paramount. Its longer blade was ideal for sweeping cuts and defending against multiple opponents.Short Sword (Wakizashi/Tantō): Designed for close-quarters combat. Indoors, where swinging a long sword was impractical, the shorter blade was far more effective. It was also the primary tool for close-range stabbing, beheading defeated opponents for identification and trophy, and for delivering the mercy stroke (coup de grâce).

- The Concept of Nitoryū (二刀流): Some schools of swordsmanship, most famously Miyamoto Musashi's Hyōhō Niten Ichi-ryū (兵法二天一流), developed techniques for simultaneously wielding both swords—the long sword for attack and distance, the short for defense and parrying. While this was a specialized skill and not the primary reason for carrying two swords, it demonstrates the tactical potential of the pair.

- Practical Necessity: A samurai would remove his long sword when entering a building, a lord's castle, or a tea house as a sign of respect and to avoid inconveniencing others in tight spaces. However, he always retained his short sword at his side. This ensured he was never completely unarmed and could defend himself even in socially delicate situations.

3. The Social and Legal Dimension: The Symbol of Status

This is the most significant reason for the systematization of the daishō.

- Exclusive Privilege: During the Edo period, the Tokugawa shogunate enacted a series of laws known as Buke Shohatto (武家諸法度, Laws for the Military Houses). Among these was the explicit right for samurai, and only samurai, to wear the daishō pair. For other social classes—farmers, artisans, and merchants—it was illegal to wear even one long sword.

- The Ie (家) and Honor: The swords were not just weapons; they were the physical embodiment of the samurai's honor and his family lineage (ie). The long sword was often a sacred family heirloom, passed down through generations. The short sword was considered the personal sword, used to defend that honor unto death.

- Visual Identifier: The daishō was an immediate, unmistakable visual marker of a man's membership in the ruling samurai class. It set him apart from the rest of society and constantly reinforced the social hierarchy.

4. The Symbolic and Spiritual Significance

The two swords represented the soul and the moral code of the warrior.

- The Soul of the Samurai: The famous saying "The sword is the soul of the samurai" (Bushi no tamashii, ken ni kakeru - 武士の魂、剣に懸ける) underscores this. To surrender one's sword was to surrender one's identity and honor.

- Dual Symbolism: The pair was sometimes interpreted to represent different aspects of the samurai's duty or the Buddhist concept of duality:The long sword (katana) was the weapon for fighting against external enemies and upholding the lord's justice.The short sword (wakizashi or tantō) was the instrument for fighting against internal failure and personal dishonor. Its most sacred and dreaded function was in the ritual of seppuku (切腹) or harakiri: ritual suicide to restore honor, avoid capture, or atone for failure. The use of one's own sword for this act was the ultimate expression of taking personal responsibility.

Historical Evolution

It is crucial to understand that the daishō custom evolved over time:

- Pre-Edo Period: On the battlefields of the Sengoku (Warring States) period, samurai would often carry a tachi and a tantō, or later a katana and a wakizashi, but it was not yet a legally codified, universal symbol. practicality was the primary driver.

- Edo Period: With the establishment of peace under the Tokugawa shogunate, the role of the samurai shifted from battlefield warrior to government bureaucrat and peacekeeper. The sword lost some of its practical military function and gained even greater importance as a symbol of social status and personal honor. The daishō became the unchallenged badge of the class.

Professional Conclusion

The samurai carried two swords for a confluence of reasons, each layer adding depth to the practice:

- Practicality: It provided a versatile armament for both open-field battles and close-quarters encounters, ensuring the warrior was never without an appropriate weapon.

- Social Law: It was a legally enforced privilege that visually distinguished the samurai estate from all other social classes, cementing their place at the top of the feudal hierarchy.

- Symbolism: It represented the dual aspects of the samurai's existence: the long sword for duty to the lord and engagement with the external world, and the short sword for personal honor, introspection, and the ultimate accountability of seppuku.

The daishō was, therefore, far more than a weapon system. It was the ultimate expression of the samurai's identity, encompassing his legal rights, social standing, martial philosophy, and personal honor in one, inseparable pair.

Why did Japan ban samurai?

Why did Japan ban samurai?

The Abolition of the Samurai Class: A Historical and Structural Analysis

The question "Why did Japan ban samurai?" requires a nuanced answer. Japan did not simply "ban" samurai in a single event. Rather, it systematically dismantled the entire feudal socio-economic-political structure that defined and supported the samurai class over a period of about two decades. This process was a necessary and deliberate consequence of the Meiji Restoration (明治維新), which aimed to transform Japan from a feudal shogunate into a modern, centralized nation-state capable of resisting Western imperialism.

The dissolution of the samurai was not an act of spite but a pragmatic, albeit painful, series of reforms essential for national survival.

1. The Pre-Meiji Context: A System in Crisis

To understand the abolition, one must first understand the samurai's role in the Tokugawa period (1603-1868).

- Peacetime Warriors: After centuries of civil war, the Tokugawa shogunate enforced a prolonged peace (Pax Tokugawa). The samurai, whose raison d'être was warfare, were gradually transformed into a hereditary class of bureaucrats, administrators, and stipend-receiving retainers for their feudal lords (daimyō).

- Financial Insolvency: The samurai were paid fixed stipends (koku) in rice from their lord's domain. However, the economy was monetizing. Many samurai, particularly low-ranking ones, fell into severe poverty and debt to merchant classes, creating widespread resentment and weakening the feudal economic model.

- Inefficiency and Fragmentation: The bakuhan system—a decentralized system of over 250 semi-autonomous domains (han) under the Shogun—was increasingly seen as inefficient. It hindered unified national policy, especially in response to the threat of Western powers demanding Japan open its ports.

2. The Meiji Restoration: The Catalyst for Change

The arrival of Commodore Perry's "Black Ships" in 1853 exposed the military and technological weakness of the Shogunate. The ensuing political crisis led to the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the restoration of imperial rule in 1868 under the young Emperor Meiji. The new Meiji government was dominated by reformist, lower-ranking samurai from powerful domains like Satsuma and Chōshū. Their goal was not to destroy Japan but to save it by building a "rich country, strong military" (富国強兵, fukoku kyōhei).

The samurai system was incompatible with this goal for several reasons, illustrated in the flowchart above.

3. The Sequential Dismantling of Samurai Privileges

The Meiji government did not immediately abolish the class. Instead, it enacted a series of calculated reforms that systematically stripped away the four pillars of samurai identity: political power, military monopoly, economic base, and social status.

1. Abolition of the Feudal Domains (廃藩置県 - Haihan Chiken), 1871:

- The Reform: The government abolished the autonomous feudal domains (han) and replaced them with centrally administered prefectures (ken). The daimyō were removed from power and relocated to Tokyo.

- Impact on Samurai: This destroyed the political foundation of the samurai class. Samurai were now stateless; they were no longer retainers of a local lord but subjects of the national government. Their traditional role as domain officials and administrators was made obsolete by a new, national civil service.

2. Creation of a National Conscript Army (徴兵令 - Chōheirei), 1873:

- The Reform: Perhaps the most symbolic blow, this ordinance established a national army based on universal conscription. All male citizens, regardless of social class (peasant, merchant, former samurai), were obligated to serve.

- Impact on Samurai: This eliminated the samurai's monopoly on violence and their raison d'être as a warrior class. The new army was trained in Western tactics and used modern firearms, making the individual skill of a swordsman obsolete. The government stated that henceforth, "the entire nation shall serve as an army," breaking a centuries-old tradition.

3. Elimination of the Stipend (秩禄処分 - Chitsuroku Shobun), 1873-1876:

- The Reform: The government commuted the samurais' hereditary stipends into one-time lump-sum payments in the form of government bonds. This was a massive financial burden on the state, and ending it was a fiscal necessity.

- Impact on Samurai: This destroyed the economic foundation of the samurai class. While some astute former samurai invested their bonds and became successful businessmen or capitalists, the vast majority lacked commercial experience and quickly squandered their money, plunging into poverty. This reform transferred wealth from the warrior class to the state and the emerging financial sector.

4. The Sword Abolishment Edict (廃刀令 - Haitōrei), 1876:

- The Reform: This edict prohibited anyone except members of the military and law enforcement from wearing swords in public.

- Impact on Samurai: This was the final, crushing blow to social identity. The right to wear two swords (daishō) was the ultimate visible symbol of samurai status and privilege. Stripping them of this right publicly and legally signaled the absolute end of their era. They were now legally indistinguishable from commoners.

4. Resistance and Final Outcome

Unsurprisingly, these reforms provoked fierce resistance from more conservative samurai who saw their world being destroyed. This culminated in the Satsuma Rebellion (西南戦争 - Seinan Sensō) in 1877, led by the iconic Saigō Takamori. This was a last, desperate stand by a disaffected faction of the samurai class.

The rebellion was brutally crushed by the new, mass-conscripted Imperial Army—a stark demonstration that the new system was superior to the old. The defeat of Saigō marked the definitive end of any serious political or military threat from the traditional samurai class.

Conclusion: A Necessary Modernization

Japan did not "ban samurai" out of malice. The Meiji oligarchs, many of whom were samurai themselves, made a calculated series of decisions to dismantle the feudal class structure. They did so because it was incompatible with the creation of a modern, centralized, and powerful nation-state.

The samurai system was:

- Politically fragmented (loyalty to domains, not the nation).

- Economically unsustainable (draining state coffers with stipends).

- Militarily obsolete (against Western-style conscript armies with modern artillery and rifles).

- Socially rigid (preventing talent-based mobility needed for modernization).

The abolition of the samurai was the painful but necessary price Japan paid to escape colonization and transform itself into a world power. The class was not banned by a single law but made extinct through a comprehensive program of structural modernization that rendered its very existence redundant. The soul of the samurai ethic, however, was later co-opted and channeled into the imperial military and national ideology, but the class itself was forever gone.